While Bitcoin can support strong privacy, many ways of using it are usually not very private. With a proper understanding of the technology, bitcoin can indeed be used in a very private and anonymous way.

This article was published on en.bitcoin.it wiki.

As of 2019 most casual enthusiasts of bitcoin believe it is perfectly traceable; this is completely false. Around 2011 most casual enthusiasts believed it is totally private; which is also false. There is some nuance - in certain situations, bitcoin can be very private. But it is not simple to understand, and it takes some time and reading.

This article was written in February 2019. A good way to read the article is to skip to the examples and then come back to read the core concepts.

Summary #

To save you reading the rest of the article, here is a quick summary of how normal bitcoin users can improve their privacy:

- Think about what you’re hiding from, what is your threat model and what is your adversary. Note that transaction surveillance companies exist which do large-scale surveillance of the bitcoin ecosystem.

- Do not reuse addresses. Addresses should be shown to one entity to receive money, and never used again after the money from them is spent.

- Try to reveal as little information as possible about yourself when transacting, for example, avoid AML/KYC checks and be careful when giving your real-life mail address.

- Use a wallet backed by your own full node or client-side block filtering, definitely not a web wallet.

- Broadcast on-chain transactions over Tor, if your wallet doesn’t support it then copy-paste the transaction hex data into a web broadcasting form over Tor browser.

- Use Lightning Network as much as possible.

- If lightning is unavailable, use a wallet that correctly implements CoinJoin.

- Try to avoid creating change addresses, for example when funding a lightning channel spend an entire UTXO into it without any change (assuming the amount is not too large to be safe).

- If digital forensics are a concern then use a solution like Tails Operating System.

See also the privacy examples for real-life case-studies.

Introduction #

Users interact with bitcoin through software which may leak information about them in various ways that damage their anonymity.

Bitcoin records transactions on the block chain which is visible to all and so creates the most serious damage to privacy. Bitcoins move between addresses; sender addresses are known, receiver addresses are known, and amounts are known. Only the identity of each address is not known (see first image).

The linkages between addresses made by transactions are often called the transaction graph. Alone, this information can’t identify anyone because the addresses and transaction IDs are just random numbers. However, if any of the addresses in a transaction’s past or future can be tied to an actual identity, it might be possible to work from that point and deduce who may own all of the other addresses. This identification of an address might come from network analysis, surveillance, searching the web, or a variety of other methods. The encouraged practice of using a new address for every transaction is intended to make this attack more difficult.

The flow of Bitcoins is highly public.

Example - Adversary controls source and destination of coins #

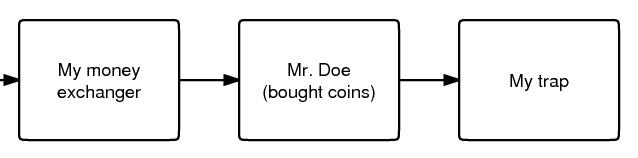

The second image shows a simple example. An adversary runs both a money exchanger and a honeypot website meant to trap people. If someone uses their exchanger to buy bitcoins and then transacts the coins to the trap website, the block chain would show:

Finding an identity of one address allows you to attack the anonymity of the transactions.

- Transaction of coins on address A to address B. Authorized by <signature of address A>.

- Transaction of coins on address B to address C. Authorized by <signature of address B>.

Say that the adversary knows that Mr. Doe’s bank account sent the government currency which were used to buy the coins, which were then transferred to address B. The adversary also knows the trap website received coins on address C that were spent from address B. Together this is a very strong indication that address B is owned by Mr. Doe and that he sent money to the trap website. This assumption is not always correct because address B may have been an address held on behalf of Mr. Doe by a third party and the transaction to C may have been unrelated, or the two transactions may actually involve a smart contract (See Off-Chain Transactions) which effectively teleports the coins off-chain to a completely different address somewhere on the blockchain.

Example - Non-anonymous Chinese newspaper buying #

In this example, the adversary controls the destination and finds the source from metadata.

- You live in China and want to buy a “real” online newspaper for Bitcoins.

- You join the Bitcoin forum and use your address as a signature. Since you are very helpful, you manage to get a modest sum as donations after a few months.

- Unfortunately, you choose poorly in who you buy the newspaper from: you’ve chosen a government agent!

- The government agent looks at the transaction used to purchase the newspaper on the block chain, and searches the web every relevant address in it. He finds your address in your signature on the Bitcoin forum. You’ve left enough personal information in your posts to be identified, so you are now scheduled to be “reeducated”.

- A major reason this happened is because of address reuse. Your forum signature had a single bitcoin address that never changed, so it was easy to find by searching the web.

You need to protect yourself from both forward attacks (getting something that identifies you using coins that you got with methods that must remain secret, like the scammer example) and reverse attacks (getting something that must remain secret using coins that identify you, like the newspaper example).

Example - A perfectly private donation #

On the other hand, here is an example of somebody using bitcoin to make a donation that is completely anonymous.

- The aim is to donate to some organization that accepts bitcoin.

- You run a Bitcoin Core wallet entirely through Tor.

- Download some extra few hundred gigabytes of data over Tor so that the total download bandwidth isn’t exactly blockchain-sized.

- Solo-mine a block, and have the newly-mined coins sent to your wallet.

- Send the entire balance to a donation address of that organization.

- Finally you destroy the computer hardware used.

As your full node wallet runs entirely over Tor, your IP address is very well hidden. Tor also hides the fact that you’re using bitcoin at all. As the coins were obtained by mining they are entirely unlinked from any other information about you. Since the transaction is a donation, there are no goods or services being sent to you, so you don’t have to reveal any delivery mail address. As the entire balance is sent, there is no change address going back that could later leak information. Since the hardware is destroyed there is no record remaining on any discarded hard drives that can later be found. The only way I can think of to attack this scheme is to be a global adversary that can exploit the known weaknessness of Tor.

Multiple interpretations of a blockchain transaction #

Bitcoin transactions are made up of inputs and outputs, of which there can be one or more. Previously-created outputs can be used as inputs for later transactions. Such outputs are destroyed when spent and new unspent outputs are usually created to replace them.

Consider this example transaction:

1 btc ----> 1 btc

3 btc 3 btc

This transaction has two inputs, worth 1 btc and 3 btc, and creates two outputs also worth 1 btc and 3 btc.

If you were to look at this on the blockchain, what would you assume is the meaning of this transaction? (for example, we usually assume a bitcoin transaction is a payment but it doesn’t have to be).

There are at least nine’ possible 1 interpretations:

- Alice provides both inputs and pays 3 btc to Bob. Alice owns the 1 btc output (i.e. it is a change output).

- Alice provides both inputs and pays 1 btc to Bob, with 3 btc paid back to Alice as the change.

- Alice provides 1 btc input and Bob provides 3 btc input, Alice gets 1 btc output and Bob gets 3 btc output. This is a kind of CoinJoin transaction.

- Alice pays 2 btc to Bob. Alice provides 3 btc input, gets the 1 btc output; Bob provides 1 btc input and gets 3 btc. This would be a PayJoin transaction type.

- Alice pays 4 btc to Bob (but using two outputs for some reason).

- Fake transaction - Alice owns all inputs and outputs, and is simply moving coins between her own addresses.

- Alice pays Bob 3 btc and Carol 1 btc. This is a batched payment with no change address.

- Alice pays 3, Bob pays 1; Carol gets 3 btc and David gets 1 btc. This is some kind of CoinJoined batched payment with no change address.

- Alice and Bob pay 4 btc to Carol (but using two outputs).

Many interpretations are possible just from such a simple transaction. Therefore it’s completely false to say that bitcoin transactions are always perfectly traceable, the reality is much more complicated.

Privacy-relevant adversaries who analyze the blockchain usually rely on heuristics (or idioms of use) where certain assumptions are made about what is plausible. The analyst would then ignore or exclude some of these possibilities. But those are only assumptions which can be wrong. Someone who wants better privacy they can intentionally break those assumptions which will completely fool an analyst.

Units of the bitcoin currency are not watermarked within a transaction (in other words they don’t have little serial numbers). For example the 1 btc input in that transaction may end up in the 1 btc output or part of the 3 btc output, or a mixture of both. Transactions are many-to-many mappings, so in a very important sense it’s impossible to answer the question of where the 1 btc ended up. This fungibility of bitcoin within one transaction is an important reason for the different possibility interpretations of the above transaction.

Threat model #

When considering privacy you need to think about exactly who you’re hiding from. You must examine how a hypothetical adversary could spy on you, what kind of information is most important to you and which technology you need to use to protect your privacy. The kind of behaviour needed to protect your privacy therefore depends on your threat model.

Newcomers to privacy often think that they can simply download some software and all their privacy concerns will be solved. This is not so. Privacy requires a change in behaviour, however slight. For example, imagine if you had a perfectly private internet where who you’re communicating with and what you say are completely private. You could still use this to communicate with a social media website to write your real name, upload a selfie and talk about what you’re doing right now. Anybody on the internet could view that information so your privacy would be ruined even though you were using perfectly private technology.

For details read the talk Opsec for Hackers by grugq. The talk is aimed mostly at political activists who need privacy from governments, but much the advice generally applies to all of us.

Much of the time plausible deniability is not good enough because lots of spying methods only need to work on a statistical level (e.g. targeted advertising).

Method of data fusion #

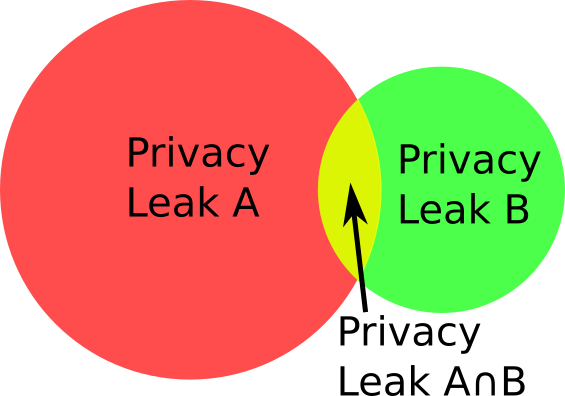

Data fusion diagram showing how two different privacy leaks can damage privacy far more in combination.

Multiple privacy leaks when combined together can be far more damaging to privacy than any single leak. Imagine if a receiver of a transaction is trying to deanonymize the sender. Each privacy leak would eliminate many candidates for who the sender is, two different privacy leaks would eliminate different candidates leaving far fewer candidates remaining. See the diagram for a diagram of this.

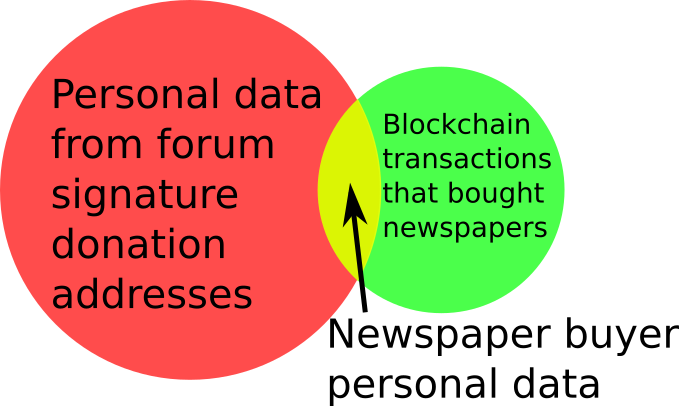

Data fusion diagram example with newspaper buyer.

This is why even leaks of a small amount of information should be avoided, as they can often completely ruin privacy when combined with other leaks. Going back to the example of the non-anonymous Chinese newspaper buyer, who was deanonymized because of a combination of visible transaction information and his forum signature donation address. There are many many transactions on the blockchain which on their own don’t reveal anything about the transactor’s identity or spending habits. There are many donation addresses placed in forum signatures which also don’t reveal much about the owners identity or spending habits, because they are just random cryptographic information. But together the two privacy leaks resulted in a trip to the reeducation camp. The method of data fusion is very important when understanding privacy in bitcoin (and other situations).

Why privacy #

Financial privacy is an essential element to fungibility in Bitcoin: if you can meaningfully distinguish one coin from another, then their fungibility is weak. If our fungibility is too weak in practice, then we cannot be decentralized: if someone important announces a list of stolen coins they won’t accept coins derived from, you must carefully check coins you accept against that list and return the ones that fail. Everyone gets stuck checking blacklists issued by various authorities because in that world we’d all not like to get stuck with bad coins. This adds friction, transactional costs and allows the blacklist provider to engage in censorship, and so makes Bitcoin less valuable as a money.

Financial privacy is an essential criteria for the efficient operation of a free market: if you run a business, you cannot effectively set prices if your suppliers and customers can see all your transactions against your will. You cannot compete effectively if your competition is tracking your sales. Individually your informational leverage is lost in your private dealings if you don’t have privacy over your accounts: if you pay your landlord in Bitcoin without enough privacy in place, your landlord will see when you’ve received a pay raise and can hit you up for more rent.

Financial privacy is essential for personal safety: if thieves can see your spending, income, and holdings, they can use that information to target and exploit you. Without privacy malicious parties have more ability to steal your identity, snatch your large purchases off your doorstep, or impersonate businesses you transact with towards you… they can tell exactly how much to try to scam you for.

Financial privacy is essential for human dignity: no one wants the snotty barista at the coffee shop or their nosy neighbors commenting on their income or spending habits. No one wants their baby-crazy in-laws asking why they’re buying contraception (or sex toys). Your employer has no business knowing what church you donate to. Only in a perfectly enlightened discrimination free world where no one has undue authority over anyone else could we retain our dignity and make our lawful transactions freely without self-censorship if we don’t have privacy.

Most importantly, financial privacy isn’t incompatible with things like law enforcement or transparency. You can always keep records, be ordered (or volunteer) to provide them to whomever, have judges hold against your interest when you can’t produce records (as is the case today). None of this requires globally visible public records.

Globally visible public records in finance are completely unheard-of. They are undesirable and arguably intolerable. The Bitcoin whitepaper made a promise of how we could get around the visibility of the ledger with pseudonymous addresses, but the ecosystem has broken that promise in a bunch of places and we ought to fix it. Bitcoin could have coded your name or IP address into every transaction. It didn’t. The whitepaper even has a section on privacy. It’s incorrect to say that Bitcoin isn’t focused on privacy. Sufficient privacy is an essential prerequisite for a viable digital currency 2.

Blockchain attacks on privacy #

Bitcoin uses a block chain. Users can download and verify the blockchain to check that all the rules of bitcoin were followed throughout its history. For example, users can check that nobody printed infinite bitcoins and that every coin was only spent with a valid signature created by its private key. This is what leads to bitcoin’s unique value proposition as a form of electronic cash which requires only small amounts of trust. But the same blockchain structure leads to privacy problems because every transaction must be available for all to see, forever. This section discusses known methods an adversary may use for analyzing the public blockchain.

Bitcoin uses a UTXO model. Transactions have inputs and outputs, they can have one or more of each. Previous outputs can be used as inputs for later transactions. An output which hasn’t been spent yet is called an unspent transaction output (UTXO). UXTOs are often called “coins”. UTXOs are associated with a bitcoin address and can be spent by creating a valid signature corresponding to the scriptPubKey of the address.

Addresses are cryptographic information, essentially random numbers. On their own they do not reveal much about the real owner of any bitcoins on them. Usually an adversary will try to link together multiple addresses which they believe belong to the same wallet. Such address collections are called “clusters”, “closures” or “wallet clusters”, and the activity of creating them is called “wallet clustering”. Once the clusters are obtained the adversary can try to link them real-world identities of entities it wants to spy on. For example, it may find wallet cluster A belonging to Alice and another wallet cluster B belonging to Bob. If a bitcoin transaction is seen paying from cluster A to cluster B then the adversary knows that Alice has sent coins to Bob.

It can be very difficult to fine-tune heuristics for wallet clustering that lead to obtaining actually correct information 3.

Common-input-ownership heuristic #

This is a heuristic or assumption which says that if a transaction has more than one input then all those inputs are owned by the same entity.

For example, consider this transaction with inputs A, B and C; and outputs X and Y.

A (1 btc) --> X (4 btc)

B (2 btc) Y (2 btc)

C (3 btc)

This transaction would be an indication that addresses B and C are owned by the same person who owns address A.

One of the purposes of CoinJoin is to break this heuristic. Nonetheless this heuristic is very commonly true and it is widely used by transaction surveillance companies and other adversaries as of 2019. The heuristic is usually combined with address reuse reasoning, which along with the somewhat-centralized bitcoin economy as of 2018 is why this heuristic can be unreasonably effective 4. The heuristic’s success also depends on the wallet behaviour: for example, if a wallet usually receives small amounts and sends large amounts then it will create many multi-input transactions.

Change address detection #

Many bitcoin transactions have change outputs. It would be a serious privacy leak if the change address can be somehow found, as it would link the ownership of the (now spent) inputs with a new output. Change outputs can be very effective when combined with other privacy leaks like the common-input-ownership heuristic or address reuse. Change address detection allows the adversary to cluster together newly created address, which the common-input-ownership heuristic and address reuse allows past addresses to be clustered.

Change addresses lead to a common usage pattern called the peeling chain. It is seen after a large transactions from exchanges, marketplaces, mining pools and salary payments. In a peeling chain, a single address begins with a relatively large amount of bitcoins. A smaller amount is then peeled off this larger amount, creating a transaction in which a small amount is transferred to one address, and the remainder is transferred to a one-time change address. This process is repeated - potentially for hundreds or thousands of hops - until the larger amount is pared down, at which point (in one usage) the amount remaining in the address might be aggregated with other such addresses to again yield a large amount in a single address, and the peeling process begins again 5.

Now are listed possible ways to infer which of the outputs of a transaction is the change output:

Address reuse #

If an output address has been reused it is very likely to be a payment output, not a change output. This is because change addresses are created automatically by wallet software but payment addresses are manually sent between humans. The address reuse would happen because the human user reused an address out of ignorance or apathy. This heuristic is probably the most accurate, as it is very hard to imagine how false positives would arise (except by intentional design of wallets). This heuristic is also called the “shadow heuristic”.

Some very old software (from the 2010-2011 era which did not have Deterministic wallets) did not use a new address change but sent the change back to the input address. This reveals the change address exactly.

Avoiding address reuse is an obvious remedy. Another idea is that those wallets could automatically detect when a payment address has been used before (perhaps by asking the user) and then use a reused address as their change address; so both outputs would be reused addresses.

Also, most reused addresses are mentioned on the internet, forums, social networks like Facebook, Reddit, Stackoverflow…etc. These addresses you can find and check on https://checkbitcoinaddress.com/ site. It’s like a little bit de-anonymization of pseudo-anonymized blockchain.

Wallet fingerprinting #

A careful analyst sometimes deduce which software created a certain transaction, because the many different wallet softwares don’t always create transactions in exactly the same way. Wallet fingerprinting can be used to detect change outputs because a change output is the one spent with the same wallet fingerprint.

As an example, consider five typical transactions that consume one input each and produce two outputs. A, B, C, D, E refer to transactions. A1, A2, etc refer to output addresses of those transactions

--> C1

A1 --> B1 --> C2

--> B2 --> D1

--> D2 --> E1

--> E2

If wallet fingerprinting finds that transactions A, B, D and E are created by the same wallet software, and the other transactions are created by other software, then the change addresses become obvious. The same transactions with non-matching addresses replaced by X is shown. The peel chain is visible, it’s clear that B2, D2, E1 are change addresses which belong to the same wallet as A1.

--> X

A1 --> X --> X

--> B2 --> X

--> D2 --> E1

--> X

There are a number of ways to get evidence used for identifying wallet software:

Address formats. Wallets generally only use one address type. If a transaction has all inputs and one output of the same address type (e.g. p2pkh), with the remaining output of a different type (p2sh), then a reasonable assumption is that the same-address-format output (p2pkh) is change and the different-address-format output (p2sh) is the payment which belongs to someone else.

Script types. Each wallet generally uses only one script. For example, the sending wallet may be a P2SH 2-of-3 multisignature wallet, which makes a transaction to two outputs: one 2-of-3 multisignature address and the other 2-of-2 multisignature address. The different script is a strong indication that the output is payment and the other output is change.

BIP69 Lexicographical Indexing of Transaction Inputs and Outputs. This BIP describes a standard way for wallets to order their inputs and outputs for privacy. Right now the wallet ecosystem has a mixture of wallets which do and don’t implement the standard, which helps with fingerprinting. Note that the common one-input-two-output transaction with random ordering will follow BIP69 just by chance 50% of the time.

Number of inputs and outputs. Different users often construct transactions differently. For example, individuals often make transaction with just two outputs; a payment and change, while high-volume institutions like casinos or exchanges use consolidation and batching 6 7. An output that is later use to create a batching transaction was probably not the change. This heuristic is also called the “consumer heuristic”.

Transaction fields. Values in the transaction format which may vary depending on the wallet software: nLockTime is a field in transactions set by some wallets to make fee sniping less profitable. A mixture of wallets in the ecosystem do and don’t implement this feature. nLockTime can also be used as in certain privacy protocols like CoinSwap. nSequence is another example. Also the version number.

Low-R value signatures. The DER format used to encode Bitcoin signatures requires adding an entire extra byte to a signature just to indicate when the signature’s R value is on the top-half of the elliptical curve used for Bitcoin. The R value is randomly derived, so half of all signatures have this extra byte. As of July 2018 8 Bitcoin Core only generates signatures with a low-R value that don’t require this extra byte. By doing so, Bitcoin Core transactions will save one byte per every two signatures (on average). As of 2019 no other wallet does this, so a high-R signature is evidence that Bitcoin Core is not being used 9.

Uncompressed and compressed public keys. Older wallet software uses uncompressed public keys 10. A mixture of compressed and uncompressed keys can be used for fingerprinting.

Miner fees. Various wallet softwares may respond to block space pressure in different ways which could lead to different kinds of miner fees being paid. This might also be a way of fingerprinting wallets.

Coin Selection. Various wallet softwares may choose which UTXOs to spend using different algorithms that could be used for fingerprinting.

If multiple users are using the same wallet software, then wallet fingerprinting cannot detect the change address. It is also possible that a single user owns two different wallets which use different software (for example a hot wallet and cold wallet) and then transactions between different softwares would not indicate a change of ownership. Wallet fingerprinting on its own is never decisive evidence, but as with all other privacy leaks it works best with data fusion when multiple privacy leaks are combined.

Round numbers #

Many payment amounts are round numbers, for example 1 BTC or 0.1 BTC. The leftover change amount would then be a non-round number (e.g. 1.78213974 BTC). This potentially useful for finding the change address. The amount may be a round number in another currency. The amount 2.24159873 BTC isn’t round in bitcoin but when converted to USD it may be close to $100.

Fee bumping #

BIP 0125 defines a mechanism for replacing an unconfirmed transaction with another transaction that pays a higher fee. In the context of the market for block space, a user may find their transaction isn’t confirming fast enough so they opt to “fee bump” or pay a higher miner fee. However generally the new higher miner fee will happen by reducing the change amount. So if an adversary is observing all unconfirmed transactions they could see both the earlier low-fee transaction and later high-fee transaction, and the output with the reduced amount would be the change output.

This could be mitigated by some of the time reducing the amount of both outputs, reducing the payment amount instead of change (in a receiver-pays-for-fee model), or replacing both addresses in each RBF transaction (this would require obtaining multiple payment addresses from the receiver).

Unnecessary input heuristic #

Also called the “optimal change heuristic”. Consider this bitcoin transaction. It has two inputs worth 2 BTC and 3 BTC and two outputs worth 4 BTC and 1 BTC.

2 btc --> 4 btc

3 btc 1 btc

Assuming one of the outputs is change and the other output is the payment. There are two interpretations: the payment output is either the 4 BTC output or the 1 BTC output. But if the 1 BTC output is the payment amount then the 3 BTC input is unnecessary, as the wallet could have spent only the 2 BTC input and paid lower miner fees for doing so. This is an indication that the real payment output is 4 BTC and that 1 BTC is the change output.

This is an issue for transactions which have more than one input. One way to fix this leak is to add more inputs until the change output is higher than any input, for example:

2 btc --> 4 btc

3 btc 6 btc

5 btc

Now both interpretations imply that some inputs are unnecessary. Unfortunately this costs more in miner fees and can only be done if the wallet actually owns other UTXOs.

Some wallets have a coin selection algorithm which violates this heuristic. An example might be because the wallets want to consolidate inputs in times of cheap miner fees. So this heuristic is not decisive evidence.

Sending to a different script type #

Sending funds to a different script type than the one you’re spending from makes it easier to tell which output is the change.

For example, for a transaction with 1 input spending a p2pkh coin and creating 2 outputs, one of p2pkh and one of p2sh, it is very likely that the p2pkh output is the change while the p2sh one is the payment.

This is also possible if the inputs are of mixed types (created by wallets supporting multiple script types for backwards compatibility). If one of the output script types is known to be used by the wallet (because the same script type is spent by at least one of the inputs) while the other is not, the other one is likely to be the payment.

This has the most effect on early adopters of new wallet technology, like p2sh or segwit. The more rare it is to pay to people using the same script type as you do, the more you leak the identity of your change output. This will improve over time as the new technology gains wider adoption.

Wallet bugs #

Some wallet software handles change in a very un-private way. For example certain old wallets would always put the change output in last place in the transaction. An old version of Bitcoin Core would add input UTXOs to the transaction until the change amount was around 0.1 BTC, so an amount of slightly over 0.1 BTC would always be change.

Equal-output CoinJoin #

Equal-output-CoinJoin transactions trivially reveal the change address because it is the outputs which are not equal-valued. For example consider this equal-output-coinjoin:

A (1btc)

X (5btc) ---> B (1btc)

Y (3btc) C (4btc)

D (2btc)

There is a very strong indication that output D is change belongs to the owner of input Y, while output C is change belonging to input X. However, CoinJoin breaks the common-input-ownership heuristic and effectively hides the ownership of payment outputs (A and B), so the tradeoffs are still heavily in favour of using coinjoin.

Cluster growth #

Wallet clusters created by using the common-input-ownership heuristic usually grow (in number of addresses) slowly and incrementally 11. Two large clusters merging is rare and may indicate that the heuristics are flawed. So another way to deduce the change address is to find which output causes the clusters to grow only slowly. The exact value for “how slowly” a cluster is allowed to grow is an open question.

Transaction graph heuristic #

As described in the introduction, addresses are connected together by transactions on the block chain. The mathematical concept of a graph can be used to describe the structure where addresses are connected with transactions. Addresses are vertices while transactions are edges in this transaction graph.

This is called a heuristic because transactions on the block chain do not necessarily correspond to real economic transactions. For example the transaction may represent someone sending bitcoins to themselves. Also, real economic transactions may not appear on the block chain but be off-chain; either via a custodial entity like an exchange, or non-custodial off-chain like Lightning Network.

Taint analysis #

Taint analysis is a technique sometimes used to study the flow of bitcoins and extract privacy-relevant information. If an address A is connected to privacy-relevant information (such as a real name) and it makes a transaction sending coins to address B, then address B is said to be tainted with coins from address A. In this way taint is spread by “touching” via transactions 12. It is unclear how useful taint analysis is for spying, as it does not take into account transfer of ownership. For example an owner of tainted coins may donate some of them to some charity, the donated coins could be said to be tainted yet the charity does not care and could not give any information about the source of those coins. Taint analysis may only be useful for breaking schemes where someone tries to hide the origin of coins by sending dozens of fake transactions to themselves many times.

Amount #

Blockchain transactions contain amount information of the transaction inputs and outputs, as well as an implicit amount of the miner fee. This is visible to all.

Often the payment amount of a transaction is a round number, possibly when converted to another currency. An analysis of round numbers in bitcoin transactions has been used to measure the countries or regions where payment have happened 13.

Input amounts revealing sender wealth #

A mismatch in the sizes of available input vs what is required can result in a privacy leak of the total wealth of the sender. For example, when intending to send 1 bitcoins to somebody a user may only have an input worth 10 bitcoins. They create a transaction with 1 bitcoin going to the recipient and 9 bitcoins going to a change address. The recipient can look at the transaction on the blockchain and deduce that the sender owned at least 10 bitcoins.

By analogy with paper money, if you hand over a 100 USD note to pay for a drink costing only 5 USD the bartender learns that your balance is at least 95 USD. It may well be higher of course, but it’s at least not lower 14.

Exact payment amounts (no change) #

Payments that send exact amounts and take no change are a likely indication that the bitcoins didn’t move hands.

This usually means that the user used the “send maximum amount” wallet feature to transfer funds to her new wallet, to an exchange account, to fund a lightning channel, or other similar cases where the bitcoins remain under the same ownership.

Other possible reasons for sending exact amounts with no change is that the coin-selection algorithm was smart and lucky enough to find a suitable set of inputs for the intended payment amount that didn’t require change (or required a change amount that is negligible enough to waive), or advanced users using manual coin selection to explicitly avoid change.

Batching #

Payment batching is a technique to reduce the miner fee of a payment. It works by batching up several payments into one block chain transaction. It is typically used by exchanges, casinos and other high-volume spenders.

The privacy implication comes in that recipients can see the amount and address of recipients 15.

When you receive your withdrawal from Kraken, you can look up your transaction on a block chain explorer and see the addresses of everyone else who received a payment in the same transaction. You don’t know who those recipients are, but you do know they received bitcoins from Kraken the same as you.

That’s not good for privacy, but it’s also perhaps not the worst thing. If Kraken made each of those payments separately, they might still be connected together through the change outputs and perhaps also by certain other identifying characteristics that block chain analysis companies and private individuals use to fingerprint particular spenders.

However, it is something to keep in mind if you’re considering batching payments where privacy might be especially important or already somewhat weak, such as making payroll in a small company where you don’t want each employee to learn the other employees’ salaries.

Unusual scripts #

Most but not all bitcoin scripts are single-signature. Other scripts are possible with the most common being multisignature. A script which is particularly unusual can leak information simply by being so unique.

2-of-3 multisig is by far the most common non-single-signature script as of 2019.

Mystery shopper payment #

A mystery shopper payment is when an adversary pays bitcoin to a target in order to obtain privacy-relevant information. It will work even if address reuse is avoided. For example, if the target is an online merchant then the adversary could buy a small item. On the payment interface they would be shown one of the merchant’s bitcoin addresses. The adversary now knows that this address belongs to the merchant and by watching the blockchain for later transactions other information would be revealed, which when combined with other techniques could reveal a lot of data about the merchant. The common-input-ownership heuristic and change address detection could reveal other addresses belonging to the merchant (assuming countermeasures like CoinJoin are not used) and could give a lower-bound for the sales volume. This works because anybody on the entire internet can request one of the merchant’s addresses.

Forced address reuse #

Forced address reuse is when an adversary pays an (often small) amount of bitcoin to addresses that have already been used on the block chain. The adversary hopes that users or their wallet software will use these forced payments as inputs to a larger transaction which will reveal other addresses via the the common-input-ownership heuristic and thereby leak more privacy-relevant information. These payments can be understood as a way to coerce the address owner into unintentional address reuse 16 17.

This attack is sometimes incorrectly called a dust attack 18.

If the forced-payment coins have landed on already-used empty addresses, then the correct behaviour by wallets is to not spend those coins ever. If the coins have landed on addresses which are not empty, then the correct behaviour by wallets is to fully-spend all the coins on that address in the same transaction.

Amount correlation #

Amounts correlation refers to searching the entire block chain for output amounts.

For example, say we’re using any black box privacy technology that breaks the transaction graph.

V --> [black box privacy tech] --> V - fee

The privacy tech is used to mix V amount of bitcoins, and it returns V bitcoins minus fees back to the user. Amount correlation could be used to unmix this tech by searching the blockchain for transactions with an output amount close to V.

A way to resist amount correlation is to split up the sending of bitcoins back to user into many transactions with output amounts (w0, w1, w2) which together add up to V minus fees.

V --> [privacy tech] --> w0

--> w1

--> w2

Another way of using amount correlation is to use it to find a starting point. For example, if Bob wants to spy on Alice. Say that Alice happens to mention in passing that she’s going on holiday costing $5000 with her boyfriend, Bob can search all transactions on the blockchain in the right time period and find transactions with output amounts close to $5000. Even if multiple matches are found it still gives Bob a good idea of which bitcoin addresses belong to Alice.

Timing correlation #

Timing correlation refers to using the time information of transactions on the blockchain. Similar to amount correlation, if an adversary somehow finds out the time that an interesting transaction happened they can search the blockchain in that time period to narrow down their candidates.

This can be beaten by uniform-randomly choosing a time between now and an appropriate time_period in which to broadcast the bitcoin transaction. This forces an adversary to search much more of the existing transactions; they have to equally consider the entire anonymity set between now and time_period.

Non-blockchain attacks on privacy #

Traffic analysis #

Bitcoin nodes communicate with each other via a peer-to-peer network to transmit transactions and blocks. Nodes relay these packets to all their connections, which has good privacy properties because a connected node doesn’t know whether the transmitted data originated from its peer or whether the peer was merely relaying it.

An adversary able to snoop on your internet connection (such as your government, ISP, Wifi provider or VPN provider) can see data sent and received by your node. This would reveal that you are a bitcoin user. Even if a connection is encrypted the adversary could still see the timings and sizes of data packets. A block being mined results in a largely synchronized burst of identically-sized traffic for every bitcoin node, because of this bitcoin nodes are very vulnerable to traffic analysis revealing the fact that bitcoin is being used.

If the adversary sees a transaction or block coming out of your node which did not previously enter, then it can know with near-certainty that the transaction was made by you or the block was mined by you. As internet connections are involved, the adversary will be able to link the IP address with the discovered bitcoin information.

A certain kind of sybil attack can be used to discover the source of a transaction or block without the adversary entirely controlling the victims internet connection. It works by the adversary creating many of their own fake nodes on different IP addresses which aggressively announce themselves in an effort to attract more nodes to connect to them, they also try to connect to as many other listening nodes as they can. This high connectivity help the adversary to locate the source newly-broadcasted transactions and blocks by tracking them as they propagate through the network 19 20 21 22. Some wallets periodically rebroadcast their unconfirmed transactions so that they are more likely to propagate widely through the network and be mined.

Some wallets are not full nodes but are lightweight nodes which function in a different way. They generally have far worse privacy properties, but how badly depends on the details of each wallet. Some lightweight wallets can be connected only to your own full node, and if that is done then their privacy with respect to traffic analysis will be improved to the level of a full node.

Custodial Wallets #

Some bitcoin wallets are just front-ends that connects to a back-end server run by some company. This kind of wallet has no privacy at all, the operating company can see all the user’s addresses and all their transactions, most of the time they’ll see the user’s IP address too. Users should not use web wallets.

Main article: Browser-based wallet

Wallet history retrieval from third-party #

All bitcoin wallets must somehow obtain information about their balance and history, which may leak information about which addresses and transactions belong to them.

Blockchain explorer websites #

Blockchain explorer websites are commonly used. Some users even search for their transaction on those websites and refresh it until it reaches 3 confirmations. This is very bad for privacy as the website can easily link the user’s IP address to their bitcoin transaction (unless Tor is used), and the queries to their website reveal that the transaction or address is of interest to somebody who has certain behavioural patterns.

To get information about your transactions it is much better to use your wallet software, not some website.

BIP 37 #

Many lightweight wallets use the BIP37 standard, which has serious design flaws leading to privacy leaks. Any wallet that uses BIP37 provides no privacy at all and is equivalent to sending all the wallets addresses to a random server. That server can easily spy on the wallet. Lessons from the failure of BIP37 can be useful when designing and understanding other privacy solutions, especially with the point about data fusion of combining BIP37 bloom filter leaks with blockchain transaction information leaks.

Main article: BIP37 privacy problems

Public Electrum servers #

Electrum is a popular software wallet which works by connecting to special purpose servers. These servers receive hashes of the bitcoin addresses in the wallet and reply with transaction information. The Electrum wallet is fast and low-resource but by default it connects to these servers which can easily spy on the user. Some other software aside from Electrum uses the public Electrum servers. As of 2019 it is a faster and better alternative for lightweight wallets than BIP37.

Servers only learn the hashes of addresses rather than addresses themselves, in practice they only know the actual address and associated transactions if it’s been used on the blockchain at least once.

It is not very difficult to run your own Electrum server and point your wallet to use only it. This restores Electrum to have the same privacy and security properties as a full node where nobody else can see which addresses or transactions the wallet is interested in. Then Electrum becomes a full node wallet.

Communication eavesdropping #

A simple but effective privacy leak. Alice gives Bob one of her addresses to receive a payment, but the communication has been eavesdropped by Eve who saw the address and now knows it belongs to Alice. The solution is to encrypt addresses where appropriate or use another way of somehow hiding them from an adversary as per the threat model.

Sometimes the eavesdropping can be very trivial, for example some forum users publish a bitcoin donation address on their website, forum signature, profile, twitter page, etc where it can be picked up by search engines. In the example of the non-anonymous Chinese newspaper buyer from the introduction, his address being publicly visible on his forum signature was a crucial part of his deanonymization. The solution here is to show each potential donator a new address, for example by setting up a web server to hand out unique addresses to each visitor.

Revealing data when transacting bitcoin #

Sometimes users may voluntarily reveal data about themselves, or be required to by the entity they interact with. For example many exchanges require users to undergo Anti-Money Laundering and Know-Your-Customer (AML/KYC) checks, which requires users to reveal all kinds of invasive personal information such as their real name, residence, occupation and income. All this information is then linked with the bitcoin addresses and transactions that are later used.

When buying goods online with bitcoin a delivery mail address is needed. This links the bitcoin transaction with the delivery address. The same applies to the user’s IP address (unless privacy technology like Tor is used).

Digital forensics #

Wallet software usually stores information it needs to operate on the disk of the computer it runs on. If an adversary has access to that disk it can extract bitcoin addresses and transactions which are known to be linked with the owner of that disk. The same disk might contain other personal information (such as a scan of an ID card). Digital forensics is one reason why all good wallet software encrypts wallet files, although that can be beaten if a weak encryption password is used.

For example if you have a bitcoin wallet installed on your PC and give the computer to a repair shop to fix, then the repair shop operator could find the wallet file and records of all your transactions. Other examples might be if an old hard disk is thrown away. Other software installed on the same computer (such as malware) can also read from disk or RAM to spy on the bitcoin transactions made by the user.

For privacy don’t leave data on your computer available to others. Exactly how depends on your threat model. Encryption and physical protection are options, as is using special operating systems like Tails OS which does not read or write from the hard drive but only uses RAM, and then deletes all data on shutdown.

Methods for improving privacy (non-blockchain) #

Obtaining bitcoins anonymously #

If the adversary has not linked your bitcoin address with your identity then privacy is much easier. Blockchain spying methods like the common-input-ownership heuristic, detecting change addresses and amount correlation are not very effective on their own if there is no starting point to link back to.

Many exchanges require users to undergo Anti-Money Laundering and Know-Your-Customer (AML/KYC) checks, which requires users to reveal all kinds of invasive personal information such as their real name, residence, occupation and income. All this information is then linked with the bitcoin addresses and transactions that are later used.

Avoiding the privacy invasion of AML/KYC is probably the single most important thing an individual can do to improve their privacy. It works far better than any actual technology like CoinJoin. Indeed all the cryptography and privacy tricks are irrelevant if all users only ever transact between AML/KYC institutions 23.

Cash trades #

Physical cash is an anonymous medium of exchange, so using it is a way to obtain bitcoin anonymously where no one except trading partners exchange identifying data.

This section won’t list websites to find such meetups because the information can go out of date, but try searching the web with “buy bitcoin for cash <your location>”. Note that some services still require ID so that is worth checking. Some services require ID only for the trader placing the advert. As of late-2018 there is at least one decentralized exchange open source project in development which aims to facilitate this kind of trading without a needing a centralized third party at all but instead using a peer-to-peer network.

Cash-in-person trades are an old and popular method. Two traders arrange to meet up somewhere and the buyer hands over cash while the seller makes a bitcoin transaction to the buyer. This is similar to other internet phenomena like Craigslist which organize meetups for exchange. Escrow can be used to improve safety or to avoid the need to wait for confirmations at the meetup.

Cash-by-mail works by having the buyer send physical cash through the mail. Escrow is always used to prevent scamming. The buyer of bitcoins can be very anonymous but the seller must reveal a mail address to the buyer. Cash-by-mail can work over long distances but does depend on the postal service infrastructure. Users should check with their local postal service if there are any guidelines around sending cash-by-mail. Often the cash can also be insured.

Cash deposit is a method where the buyer deposits cash directly into the seller’s bank account. Again escrow is used, and again the buyer of bitcoins can be near-anonymous but the seller must sign up with a bank or financial institution and share with them rather invasive details about one’s identity and financial history. This method relies on the personal banking infrastructure so works over long distances.

Cash dead drop is a rarely used method. It is similar to a cash-in-person trade but the traders never meet up. The buyer chooses a location to hide the cash in a public location, next the buyer sends a message to the seller telling them the location, finally the seller picks up the cash from the hidden location. Escrow is a requirement to avoid scamming. This method is very anonymous for the buyer as the seller won’t even learn their physical appearance, for the seller it is slightly less anonymous as the buyer can stalk the location to watch the seller collect the cash.

Cash substitute #

Cash substitutes like gift cards, mobile phone credits or prepaid debit cards can often be bought from regular stores with cash and then traded online for bitcoin.

Employment #

Bitcoins accepted as payment for work done can be anonymous if the employer does not request much personal information. This may work well in a freelancing or contracting setting. Although if your adversary is your own employer then obviously this is not good privacy.

Mining #

Mining is the most anonymous way to obtain bitcoin. This applies to solo-mining as mining pools generally know the hasher’s IP address. Depending on the size of operation mining may use a lot of electrical power which may attract suspicion. Also the specialized mining hardware may be difficult to get hold of anonymously (although they wouldn’t be linked to the resulting mined bitcoins).

Stealing #

In theory another way of obtaining anonymous bitcoin is to steal them 24.

There is at least one situation where this happened. In May 2015 a hacker known as Phineas Fisher 25 hacked a spyware company that was selling surveillance products to dictators 26. The hacker used bitcoin stolen from other people to anonymously rent infrastructure for later attacks.

Spending bitcoins anonymously #

If you give up your delivery address (which you’ll have to if you’re buying physical goods online) then that will be a data leak. Obviously this is unavoidable in many cases.

Wallet history synchronization #

Bitcoin wallets must somehow obtain information about their balance and history. As of late-2018 the most practical and private existing solutions are to use a full node wallet (which is maximally private) and client-side block filtering (which is very good).

One issue with these technologies is that they always costs more resources (time, bandwidth, storage, etc) than non-private solutions like web wallets and centralized Electrum servers. There are measurements indicating that very few people actually use BIP37 because of how slow it is 27, so even client-side block filtering may not be used very much.

Full node #

Full nodes download the entire blockchain which contains every on-chain transaction that has ever happened in bitcoin. So an adversary watching the user’s internet connection will not be able to learn which transactions or addresses the user is interested in. This is the best solution to wallet history synchronization with privacy, but unfortunately it costs a significant amount in time and bandwidth.

Private information retrieval #

In cryptography, a private information retrieval (PIR) protocol is a protocol that allows a user to retrieve an item from a server in possession of a database without revealing which item is retrieved. This has been proposed as a way to private synchronize wallet history but as PIR is so resource-intensive, users who don’t mind spending bandwidth and time could just run a full node instead.

Client-side block filtering #

Client-side block filtering works by having filters created that contains all the addresses for every transaction in a block. The filters can test whether an element is in the set; false positives are possible but not false negatives. A lightweight wallet would download all the filters for every block in the blockchain and check for matches with its own addresses. Blocks which contain matches would be downloaded in full from the peer-to-peer network, and those blocks would be used to obtain the wallet’s history and current balance.

Address query via onion routing #

Wallet histories can be obtained from centralized servers (such as Electrum servers) but using a new Tor circuit for each address. A closely-related idea is to connect together Electrum servers in an onion-routing network 28. When creating such a scheme, care should be taken to avoid timing correlation linking the addresses together, otherwise the server could use the fact that the addresses were requested close to each other in time.

Countermeasures to traffic analysis #

Bitcoin Core and its forks have countermeasures against sybil attack and eclipse attacks. Eclipse attacks are sybil attacks where the adversary attempts to control all the peers of its target and block or control access to the rest of the network 29. Such attacks have been extensively studied in a 2015 paper Eclipse Attacks on Bitcoin’s Peer-to-Peer Network which has led to new code written for Bitcoin Core for mitigation 30 31 32 33 34.

Bitcoin Core and its forks use an algorithm known as trickling when relaying unconfirmed transactions, with the aim of making it as difficult as possible for sybil attackers to find the source IP address of a transaction. For each peer, the node keeps a list of transactions that it is going to inv to it. It sends inv’s for transactions periodically with a random delay between each inv. Transactions are selected to go into the inv message somewhat randomly and according to some metrics involving fee rate. It selects a limited number of transactions to inv. The algorithm creates the possibility that a peered node may hear about an unconfirmed transaction from the creator’s neighbours rather than the creator node itself 35 36 37 38. However adversaries can still sometimes obtain privacy-relevant information.

Encrypting messages between peers as in BIP 151 would make it harder for a passive attacker such as an ISP or Wifi provider to see the exact messages sent and received by a bitcoin node.

Tor and tor broadcasting #

If a connection-controlling adversary is a concern, then bitcoin can be run entirely over Tor. Tor is encrypted and hides endpoints, so an ISP or Wifi providers won’t even know you’re using bitcoin. The other connected bitcoin nodes won’t be able to see your IP address as Tor hides it. Bitcoin Core and its forks have features to make setting up and using Tor easier. Some lightweight wallets also run entirely over Tor.

Running entirely over Tor has the downside that synchronizing the node requires downloading the entire blockchain over tor, which would be very slow. Downloading blocks over Tor only helps in the situation where you want to hide the fact that bitcoin is even being used from the internet service provider 39. It is possible to download blocks and unconfirmed transactions over clearnet but broadcast your own transactions over Tor, allowing a fast clearnet connection to be used while still providing privacy when broadcasting.

Bitcoin Core being configured with the option walletbroadcast=0 will stop transactions belonging to the user from being broadcast and rebroadcast, allowing them to be broadcast instead via Tor or another privacy-preserving method 40.

Dandelion #

Dandelion is another technology for private transaction broadcasting. The main idea is that transaction propagation proceeds in two phases: first the “stem” phase, and then “fluff” phase. During the stem phase, each node relays the transaction to a single peer. After a random number of hops along the stem, the transaction enters the fluff phase, which behaves just like ordinary transaction flooding/diffusion. Even when an attacker can identify the location of the fluff phase, it is much more difficult to identify the source of the stem 41 42 43 44.

Interactive peer broadcasting #

Some privacy technologies like CoinJoin and CoinSwap require interactivity between many bitcoin entities. They can also be used to broadcast transactions with more privacy, because peers in the privacy protocols can send each other unconfirmed transactions using the already-existing protocol they use to interact with each other.

For example, in JoinMarket market takers can send transactions to market makers who will broadcast them and so improve the taker’s privacy. This can be a more convenient for the taker than setting up Tor for use with tor broadcasting.

Receiving bitcoin data over satellite #

At least one bitcoin company offers a satellite bitcoin service 45. This is a free service where satellites broadcast the bitcoin blockchain to nearly anywhere in the world. If users set up a dish antenna pointing at a satellite in space, then they can receive bitcoin blocks needed to run a full node. As the satellite setups are receive-only nobody can detect that the user is even running bitcoin, and certainly not which addresses or transactions belong to them.

As of 2019 the company offers a paid-for API which allows broadcasting any data to anywhere in the world via satellite, which seems to be how they make their money. But it appears the base service of broadcasting the blockchain will always be free.

Main article: https://blockstream.com/satellite/

Methods for improving privacy (blockchain) #

This section describes different techniques for improving the privacy of transactions related to the permanent record of transactions on the blockchain. Some techniques are trivial and are included in all good bitcoin wallets. Others have been implemented in some open source projects or services, which may use more than one technique at a time. Other techniques have yet to be been implemented. Many of these techniques focus on breaking different heuristics and assumptions about the blockchain, so they work best when combined together.

Avoiding address reuse #

Addresses being used more than once is very damaging to privacy because that links together more blockchain transactions with proof that they were created by the same entity. The most private and secure way to use bitcoin is to send a brand new address to each person who pays you. After the received coins have been spent the address should never be used again. Also, a brand new bitcoin address should be demanded when sending bitcoin. All good bitcoin wallets have a user interface which discourages address reuse.

It has been argued that the phrase “bitcoin address” was a bad name for this object because it implies it can be reused like an email address. A better name would be something like “bitcoin invoice”.

Bitcoin isn’t anonymous but pseudonymous, and the pseudonyms are bitcoin addresses. Avoiding address reuse is like throwing away a pseudonym after its been used.

Bitcoin Core 0.17 includes an update to improve the privacy situation with address reuse 46. When an address is paid multiple times the coins from those separate payments can be spent separately which hurts privacy due to linking otherwise separate addresses. A -avoidpartialspends flag has been added (default=false), if enabled the wallet will always spend existing UTXO to the same address together even if it results in higher fees. If someone were to send coins to an address after it was used, those coins will still be included in future coin selections.

Avoiding forced address reuse #

The easiest way to avoid the privacy loss from forced address reuse to not spend coins that have landed on an already-used and empty addresses. Usually the payments are of a very low value so no relevant money is lost by simply not spending the coins.

Another option is to spend the coins individual directly to miner fees. Here are instructions for how to do this with Electrum or Bitcoin Core: https://gist.github.com/ncstdc/90fe6209a0b3ae815a6eaa2aef53524c

Dust-b-gone is an old project 47 which aimed to safely spend forced-address-reuse payments. It signs all the UTXOs together with other people’s and spends them to miner fees. The transactions use rare OP_CHECKSIG sighash flags so they can be easily eliminated from the adversary’s analysis, but at least the forced address reuse payments don’t lead to further privacy loss.

Coin control #

Coin control is a feature of some bitcoin wallets that allow the user to choose which coins are to be spent as inputs in an outgoing transaction. Coin control is aimed to avoid as much as possible transactions where privacy leaks are caused by amounts, change addresses, the transaction graph and the common-input-ownership heuristic 48 49.

An example for avoiding a transaction graph privacy leak with coin control: A user is paid bitcoin for their employment, but also sometimes buys bitcoin with cash. The user wants to donate some money to a charitable cause they feel passionately about, but doesn’t want their employer to know. The charity also has a publicly-visible donation address which can been found by web search engines. If the user paid to the charity without coin control, his wallet may use coins that came from the employer, which would allow the employer to figure out which charity the user donated to. By using coin control, the user can make sure that only coins that were obtained anonymously with cash were sent to the charity. This avoids the employer ever knowing that the user financially supports this charity.

Multiple transactions #

Paying someone with more than one on-chain transaction can greatly reduce the power of amount-based privacy attacks such as amount correlation and round numbers. For example, if the user wants to pay 5 BTC to somebody and they don’t want the 5 BTC value to be easily searched for, then they can send two transactions for the value of 2 BTC and 3 BTC which together add up to 5 BTC.

Privacy-conscious merchants and services should provide customers with more than one bitcoin address that can be paid.

Change avoidance #

Change avoidance is where transaction inputs and outputs are carefully chosen to not require a change output at all. Not having a change output is excellent for privacy, as it breaks change detection heuristics.

Change avoidance is practical for high-volume bitcoin services, which typically have a large number of inputs available to spend and a large number of required outputs for each of their customers that they’re sending money to. This kind of change avoidance also lowers miner fees because the transactions uses less block space overall.

Main article: Techniques_to_reduce_transaction_fees#Change_avoidance

Another way to avoid creating a change output is in cases where the exact amount isn’t important and an entire UTXO or group of UTXOs can be fully-spent. An example is when opening a Lightning Network payment channel. Another example would be when sweeping funds into a cold storage wallet where the exact amount may not matter.

Multiple change outputs #

If change avoidance is not an option then creating more than one change output can improve privacy. This also breaks change detection heuristics which usually assume there is only a single change output. As this method uses more block space than usual, change avoidance is preferable.

Script privacy improvements #

The script of each bitcoin output leaks privacy-relevant information. For example as of late-2018 around 70% of bitcoin addresses are single-signature and 30% are multisignature 50. Much research has gone into improving the privacy of scripts by finding ways to make several different script kinds look the same. As well as improving privacy, these ideas also improve the scalability of the system by reducing storage and bandwidth requirements.

ECDSA-2P is a cryptographic scheme which allows the creation of a 2-of-2 multisignature scheme but which results in a regular single-sig ECDSA signature when included on the blockchain 51. It doesn’t need any consensus changes because bitcoin already uses ECDSA.

Schnorr is a digital signature scheme which has many benefits over the status-quo ECDSA 52 53. One side effect is that any N-of-N 54 and M-of-N multisignature can be easily made to look like a single-sig when included on the blockchain. Adding Schnorr to bitcoin requires a Softfork consensus change. As of 2019 a design for the signature scheme has been proposed 55. The required softfork consensus change is still in the design stage as of early-2019.

Scriptless scripts are a set of cryptographic protocols which provide a way of replicating the logic of script without actually having the script conditions visible, which increases privacy and scalability by removing information from the blockchain 56 57 58 59. This is generally aimed at protocols involving Hash Time Locked Contracts such as Lightning Network and CoinSwap.

With scriptless scripts, nearly the only thing visible is the public keys and signatures. More than that, in multi-party settings, there will be a single public key and a single signature for all the actors. Everything looks the same– lightning payment channels would look the same as single-sig payments, escrows, atomic swaps, or sidechain federation pegs. Pretty much anything you think about that people are doing on bitcoin in 2019, can be made to look essentially the same 60.

MAST is short for Merkelized Abstract Syntax Tree, which is a scheme for hiding unexecuted branches of a script contract. It improves privacy and scalability by removing information from the blockchain 61 62.

Taproot is a way to combine Schnorr signatures with MAST 63. The Schnorr signature can be used to spend the coin, but also a MAST tree can be revealed only when the user wants to use it. The schnorr signature can be any N-of-N or use any scriptless script contract. The consequence of taproot is a much larger anonymity set for interesting smart contracts, as any contract such as Lightning Network, CoinSwap, multisignature, etc would appear indistinguishable from regular single-signature on-chain transaction.

The taproot scheme is so useful because it is almost always the case that interesting scripts have a logical top level branch which allows satisfaction of the contract with nothing other than a signature by all parties. Other branches would only be used where some participant is failing to cooperate.

Graftroot is a smart contract scheme similar to taproot. It allows users to include other possible scripts for spending the coin but with less resources used even than taproot. The tradeoff is that interactivity is required between the participants 64 65 66.

nLockTime is a field in the serialized transaction format. It can be used in certain situations to create a more private timelock which avoids using script opcodes.

ECDH addresses #

ECDH addresses can be used to improve privacy by helping avoid address reuse. For example, a user can publish a ECDH address as a donation address which is usable by people who want to donate. An adversary can see the ECDH donation address but won’t be able to easily find any transactions spending to and from it.

However ECDH addresses do not solve all privacy problems as they are still vulnerable to mystery shopper payments; an adversary can donate some bitcoins and watch on the blockchain to see where they go afterwards, using heuristics like the common-input-ownership heuristic to obtain more information such as donation volume and final destination of funds.

ECDH addresses have some practicality issues and are very closely equivalent to running a http website which hands out bitcoin addresses to anybody who wants to donate except without an added step of interactivity. It is therefore unclear whether ECDH are useful outside the use-case of non-interactive donations or a self-contained application which sends money to one destination without any interactivity.

Centralized mixers #

This is an old method for breaking the transaction graph. Also called “tumblers” or “washers”. A user would send bitcoins to a mixing service and the service would send different bitcoins back to the user, minus a fee. In theory an adversary observing the blockchain would be unable to link the incoming and outgoing transactions.

There are several downsides to this. The mixer it must be trusted to keep secret the linkage between the incoming and outgoing transactions. Also the mixer must be trusted not to steal coins. This risk of stealing creates reputation effects; older and more established mixers will have a better reputation and will be able to charge fees far above the marginal cost of mixing coins. Also as there is no way to sell reputation, the ecosystem of mixers will be filled with occasional exit scams.

There is a better alternative to mixers which has essentially the same privacy and custody risks. A user could deposit and then withdraw coins from any regular bitcoin website that has a hot wallet. As long as the bitcoin service doesn’t require any other information from the user, it has the same privacy and custody aspects as a centralized mixer and is also much cheaper. Examples of suitable bitcoin services are bitcoin casinos, bitcoin poker websites, tipping websites, altcoin exchanges or online marketplaces 67.

The problem of the service having full knowledge of the transactions could be remedied by cascading several services together. A user who wants to avoid tracking by passive observers of the blockchain could first send coins to a bitcoin casino, from them withdraw and send directly to an altcoin exchange, and so on until the user is happy with the privacy gained.

Main article: Bitcoin mixer

CoinJoin #

CoinJoin is a special kind of bitcoin transaction where multiple people or entities cooperate to create a single transaction involving all their inputs. It has the effect of breaking the common-input-ownership heuristic and it makes use of the inherent fungibility of bitcoin within transactions. The CoinJoin technique has been possible since the very start of bitcoin and cannot be blocked except in the ways that any other bitcoin transactions can be blocked. Just by looking at a transaction it is not possible to tell for sure whether it is a coinjoin. CoinJoins are non-custodial as they can be done without any party involved in a coinjoin being able to steal anybody else’s bitcoins 68.

Equal-output CoinJoin #

Say this transaction is a CoinJoin, meaning that the 2 BTC and 3 BTC inputs were actually owned by different entities.

2 btc --> 3 btc

3 btc 2 btc

This transaction breaks the common-input-ownership heuristic, because its inputs are not all owned by the same person but it is still easy to tell where the bitcoins of each input ended up. By looking at the amounts (and assuming that the two entities do not pay each other) it is obvious that the 2 BTC input ends up in the 2 BTC output, and the same for the 3 BTC. To really improve privacy you need CoinJoin transaction that have a more than one equal-sized output:

2 btc --> 2 btc

3 btc 2 btc

1 btc

In this transaction the two outputs of value 2 BTC cannot be linked to the inputs. They could have come from either input. This is the crux of how CoinJoin can be used to improve privacy, not so much breaking the transaction graph rather fusing it together. Note that the 1 BTC output has not gained much privacy, as it is easy to link it with the 3 BTC input. The privacy gain of these CoinJoins is compounded when the they are repeated several times.

As of late-2018 CoinJoin is the only decentralized bitcoin privacy method that has been deployed. Examples of (likely) CoinJoin transactions IDs on bitcoin’s blockchain are 402d3e1df685d1fdf82f36b220079c1bf44db227df2d676625ebcbee3f6cb22a and 85378815f6ee170aa8c26694ee2df42b99cff7fa9357f073c1192fff1f540238. Note that these coinjoins involve more than two people, so each individual user involved cannot know the true connection between inputs and outputs (unless they collude).

PayJoin #

Main article: PayJoin

The type of CoinJoin discussed in the previous section can be easily identified as such by checking for the multiple outputs with the same value. It’s important to note that such identification is always deniable, because somebody could make fake CoinJoins that have the same structure as a coinjoin transaction but are made by a single person.

PayJoin (also called pay-to-end-point or P2EP) 69 70 71 is a special type of CoinJoin between two parties where one party pays the other. The transaction then doesn’t have the distinctive multiple outputs with the same value, and so is not obviously visible as an equal-output CoinJoin. Consider this transaction:

2 btc --> 3 btc

5 btc 4 btc

It could be interpreted as a simple transaction paying to somewhere with leftover change (ignore for now the question of which output is payment and which is change). Another way to interpret this transaction is that the 2 BTC input is owned by a merchant and 5 BTC is owned by their customer, and that this transaction involves the customer paying 1 BTC to the merchant. There is no way to tell which of these two interpretations is correct. The result is a coinjoin transaction that breaks the common-input-ownership heuristic and improves privacy, but is also undetectable and indistinguishable from any regular bitcoin transaction.

If PayJoin transactions became even moderately used then it would make the common-input-ownership heuristic be completely flawed in practice. As they are undetectable we wouldn’t even know whether they are being used today. As transaction surveillance companies mostly depend on that heuristic, as of 2019 there is great excitement about the PayJoin idea 72.

CoinSwap #

Main article: CoinSwap

CoinSwap is a non-custodial privacy technique for bitcoin based on the idea of atomic swaps 73. If Alice and Bob want to do a coinswap; then it can be understood as Alice exchanging her bitcoin for the same amount (minus fees) of Bob’s bitcoins, but done with bitcoin smart contracts to eliminate the possibility of cheating by either side.

CoinSwaps break the transaction graph between the sent and received bitcoins. On the block chain it looks like two sets of completely disconnected transactions:

Alice's Address ---> escrow address 1 ---> Bob's Address

Bob's Address ---> escrow address 2 ---> Alice's Address

Obviously Alice and Bob generate new addresses each to avoid the privacy loss due to address reuse.