A report by Adamant Research.

Introduction #

At the end of the 16th century, a rag tag group of rebel intellectuals and entrepreneurs founded a country on some of the least desirable land in Europe — so often flooded that it needed hundreds of miles of moats - while fighting an eighty year long war against the largest empire in the world.

From this struggle and melting pot of ideas emerged the Dutch and British golden ages, innovative economic institutions that changed the world, as well as one of America’s most successful socio-economic experiments: New York City.

This report makes the case that the 21st century emergence of bitcoin, encryption, the internet, and millennials are more than just trends; they herald a wave of change that exhibits similar dynamics as the 16-17th century revolution that took place in Europe.

Some of the conclusions our report suggests:

- Bitcoin tolerance versus intolerance to become a major political faultline

- Bitcoin’s primary drivers will be in saving, lending and underwriting

- Collaborative custody to become an industry standard

- Offshore banking may transform into bitcoin banking

- Bitcoin to mature quickly: bonds, annuities, loans, insurance

- Initial exchange offerings (IEOs) expected to stay and grow larger

- Bitcoin savers could accelerate a revolution in the history of thought

The Past As Key To The Present - A Note On Method #

As an investor and analyst, I aim to identify socio-economic trends and predict how they will evolve. I read, curate and share. I separate signal from noise by listening to experts who I think have integrity. And yet, a major challenge remains in that secular trends often are clearly identifiable only in hindsight.

The solution, I believe, is identifying parallel historic perspectives. In order to reduce my chances of remaining a trend-blind contemporary, I study history in the broad sense. As I read history books and papers, I’m on the lookout to find parallels and symmetries with present day trends. In doing so, I stretch my mind to consider dynamics that I hadn’t previously, and am able to hypothesize about causalities that were previously inconceivable to me. I believe this improves my ability to assign probabilities to certain outcomes, which in turn allows me to strategize my investments and entrepreneurial endeavors in a more rational way.

“Whoever wishes to foresee the future must consult the past; for human events ever resemble those of preceding times. This arises from the fact that they are produced by men who ever have been, and ever will be, animated by the same passions, and thus they necessarily have the same result.”

— Niccolò Machiavelli, 1517

In the past I’ve drawn parallels between bitcoin and the early petroleum industry, the search engine wars, the domain name markets, the growth of P2P file sharing, and internet protocols. But I kept feeling that I was failing to fundamentally grasp the magnitude of the epoch in which bitcoin functions as a catalyst. It wasn’t until I studied the era around the Protestant Reformation that I felt I’d found a potential blueprint of sufficient scope.

I hope you enjoy reading this report as much as I did researching it.

Sincerely,

Tuur Demeester

Four Preconditions Of A Reformation #

We believe there were four conditions that enabled the Protestant Reformation, and we think those same four preconditions are present today: a painful status quo in the form of a monopoly service provider, technological catalysts for change, a new economic class, and credible defense and exit strategies for rebels.

1. Rent-seeking Monopolistic Service Provider #

In the 2002 paper “An Economic Analysis of the Protestant Reformation” it is argued that the Catholic Church was a monopolistic provider of spiritual services, and that the control that religious authorities had over portions of the legal system provided them with the market power to exclude rivals 1. For centuries, the Catholic Church exercised a highly regarded gatekeeper function: it controlled the keys to heaven via forgiveness of sin, typically provided by priests. The authors of the paper argue that “if the religious monopoly overcharges, it risks two forms of entry: (a) the common citizenry may choose other dispensers of religious services, and (b) the civil authorities may seek a different provider of legal services.” And this is indeed what happened during the Reformation.

In present day, the monopolistic service provider whose rent-seeking is being questioned is the International Monetary and Financial System (IMFS) 2. Since the 1944 Bretton Woods agreement, the US dollar has enjoyed the “exorbitant privilege” of being the world’s reserve currency. Similar to the Catholic Church in the 16th century, financial authorities’ control over portions of the legal system provides them with the market power to exclude rivals. In addition, the fiat-settled banking system has a gatekeeper function where it controls the keys to the wealth and pensions of the world’s citizenry. In the current environment of quantitative easing, negative interest rates, and currency wars, the banking monopoly is arguably overcharging for its services (customers are paying the inflation tax), which means it risks two forms of entry: (a) the common citizenry may choose other dispensers of financial services, and (b) the civil authorities may seek a different provider of financial services — in other words, given more adoption, we may see political entities embrace bitcoin as a full-fledged money for all legal purposes.

“Temporary levies became permanent, and many new taxes were imposed on the wealthiest church members. Church documents […] reveal that sons and grandsons of heretics had to pay up for the sins of their fathers […] the souls of deceased relatives could be extricated from purgatory for fees.”

— The Marketplace of Christianity, p. 117

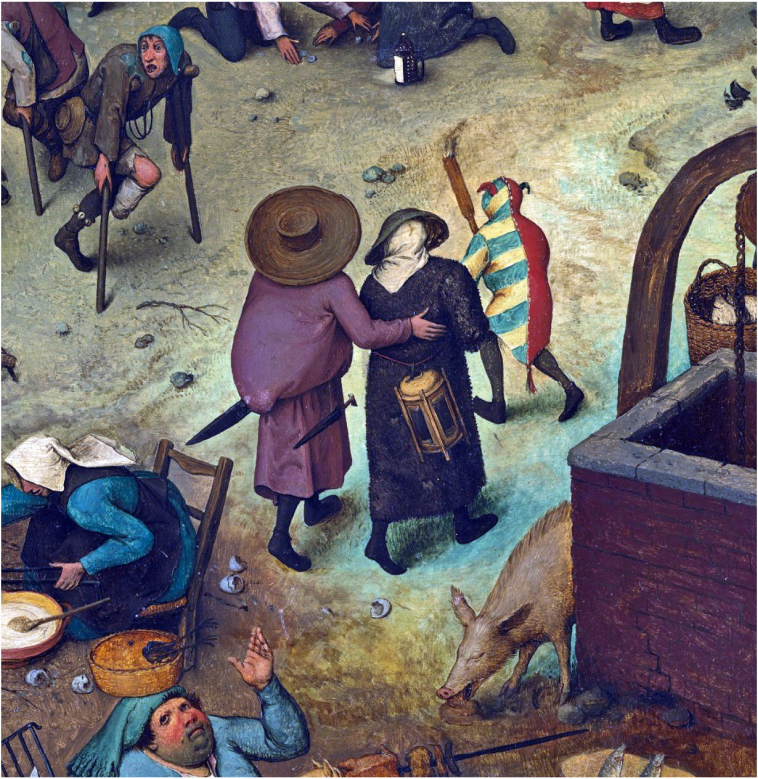

Details of “The Fight Between Carnival and Lent” by Pieter Bruegel, 1559. Breughel’s allegory captures the conflict of the century, with on the left the indulgent rebels, and on the right the weakened Catholic church.

2. Technological Revolution: Catalyst For Change #

In the 16th century, several world-changing inventions gained meaningful adoption: the printing press 3 lowered the cost of a book from a year’s labor to the price of a chicken, double entry bookkeeping 4 accelerated international commerce, compass and hourglass improvements 5 allowed for returning from unmapped territory (which unlocked world exploration), and the boom in scientific research 6 lead to the advancement of yet more inventions.

In the late 20th and early 21st century, several inventions have brought about about a digital revolution: telecommunications and email allow for working remotely, the commoditization of computation and data storage massively lowers infrastructure overhead which allows for startup costs to decline, open source software provides entrepreneurs with robust and free building tools, cryptography opens up a suite of defensive technologies for permissionless security solutions, and social media allows for rapid and non-bureaucratic dissemination of information.

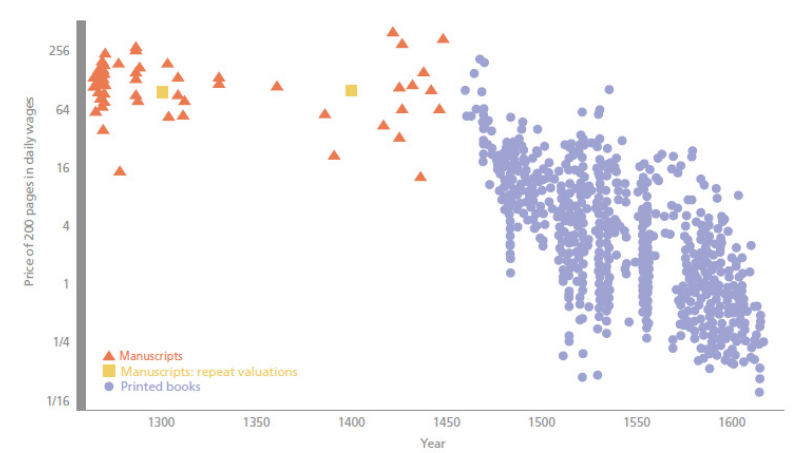

In 15th century Europe “the raw price of books fell by 2.4 per cent a year for over a hundred years,” while the share of university courses on scientific subjects rose from 25% to 40%. (Dittmar & Seabold)

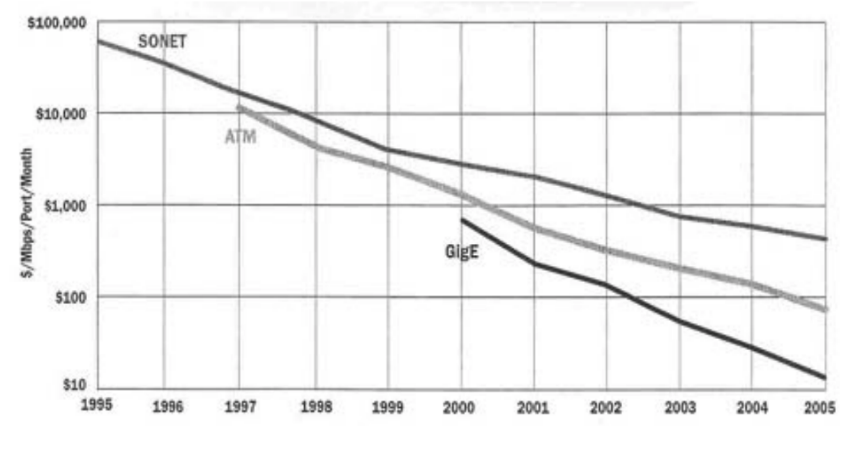

The price of a 1 megabit/s internet connection dropped by 99% in 20 years, from nearly $100K to under $10 7.

“Generally those from Antwerp are splendid and very rich merchants, […] eager to emulate the strangers […] audacious and capable of trading anywhere in the world.”

— Guicciardini, 1612

3. New Economic Class: People With Something To Fight For #

During the 16th and 17th centuries maritime trade throughout Europe improved and grew significantly 8. Flowing all the way from Switzerland to the British Channel, the Rhine river was a major artery for trade, and the cities of the Lowlands were natural beneficiaries from being located at the mouth of it. Intercontinental shipping took off as well, primarily with the spice trade between Asia and Europe. The increased volume of trade amplified the impact of technological innovation, and port cities with good rule of law saw a rise in specialized industries like painting, fabrics, book printing, weaponry, tapistry, schooling, and medicine. The specialists at the top of these industries could solicit business from all across Europe. As a result of increased trade, technological innovation, and intense specialization, overall wealth increased and the relative contribution of agriculture to the economy diminished, which weakened the wealth of landlords and churches in favor of the new merchant class.

Today, class systems in the West are less defined. However, we do believe that certain parts of the population are much more change-oriented than others. The millennial generation in particular has a distinct skepticism towards traditional finance, and enthusiastically embraces digital innovation. A 2016 survey by Facebook found that only 8% of millennials “trust financial institutions for guidance,” and that 45% are “ready to switch if a better option comes along 9.” Furthermore, a survey by the Transamerica Center for Retirement Services suggests that 76% of millennials believe that “compared to my parent’s generation, our generation will have a much harder time in achieving social security,” and 79% are also “concerned that when I am ready to retire, social security won’t be there for me 10.” Aside from being the most invested in the Bitcoin economy 11, millennials as a cohort are expected to control the largest share of disposable income by 2029 12.

“The new Millennial [birth year] cutoff of 1996 is important because it points to a generation that is old enough to have experienced and comprehend 9/11, while also finding their way through the 2008 recession as young adults.”

— Pew Research, 2018

4. Credible Strategies For Defense And Escape #

Even with superior economics on his side, and with significant wealth, a citizen will be a lot less tempted to oppose a domineering status quo if he doesn’t also have credible strategies for both defense and escape.

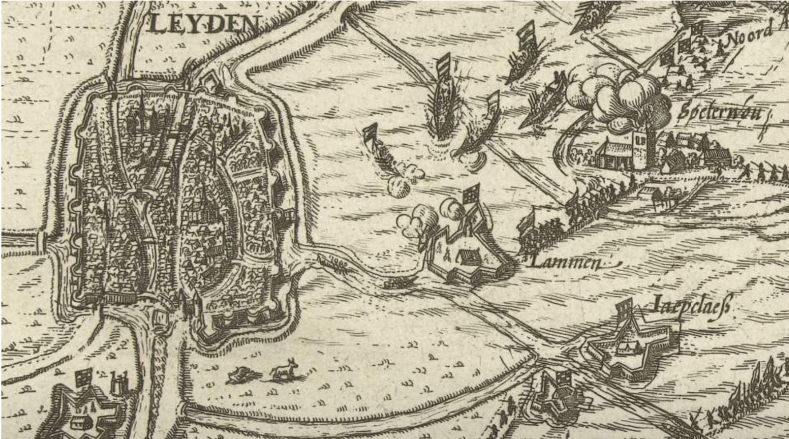

It was no coincidence that the Dutch Revolt lasted 80 years — longer than any other uprising in Modern European History. The “sea beggars” were undisputed masters of water. In 1573, the Dutch successfully defended against the siege of Alkmaar by flooding the surrounding fields. They also wiped out a critical Spanish supply line using flooding. A year later the same tactic saved the town of Leiden, the Dutch nucleus of education, from another Spanish attack. The western core of the Dutch republic was protected by a “waterline”: a string of fortified villages, close enough to allow for optic communication, with surrounding lands that could be flooded in a matter of hours. And because of easy access to the North Sea and large fleet, there were the fallback options of emigration to the British Isles or, as the 17th century came around, venturing to the New World.

“Relief of Leyden”, 1574 (detail). Breaching the dikes to flood the countryside caused huge damage, but the flood weakened the Spanish army and allowed the Dutch flotilla to reach the city.

In the 21st century, the defensive technological suite available for people who question the economic status quo is cryptography — which can enable privacy and protection from asset seizure 13. Today, encryption is very widely used. For example, the application of HTTPS on the web grew from 13% in 2014 to 77% in 2018 14. However encryption defeats the purpose of privacy if the service provider can be backdoored. We therefore see an increased interest in digital self sovereignty, with millennials adopting bitcoin, and showing interest in projects such as VPN, Blockstack, wifi mesh networks 15, Tor, Signal, Purism, U2F, PGP, and so forth.

“If conquering the other towns takes as much time as the ones we’ve already subjugated, there isn’t time or money enough in the world to overpower the 24 towns which are rebelling in Holland.”

— Spanish commander Don Luis De Requesens, 1574

“Cryptology represents the future of privacy, and by implication the future of money, and the future of banking and finance. […] Given the choice between intersecting with a monetary system that leaves a detailed electronic trail of all one’s financial activities, and a parallel system that ensures anonymity and privacy, people will opt for the latter. Moreover, they will demand the latter […]”

— Orlin Grabbe, 1995

Doctrines Then And Now #

One intuitive parallel between the Protestant Reformation and now are the doctrines which reflected the very essence of the rebellion — they were the calls of unity and conviction, and we see similar unifying doctrines today.

In the 16th century, the principal doctrine of the Lutheran Reformation was summarized with the words Sola Fide which translates to “faith alone.” This phrase encapsulated the idea that for access to heaven, believers didn’t need a priest anymore. Their faith and devotion alone would suffice. Another common call of the Reformation was Sola Scriptura, or “by scripture alone,” which signified the rejection of any original infallible authority other than the Bible.

In the bitcoin space today, there are several “battle cries” that tend to be dismissed as memes. In our view, they reflect a rebellious essence that could herald a modern-day reformation. A first is Vires in Numeris 16, which stands for “strength in numbers.” The spirit of this crede was summarized by Tyler Winklevoss in an often quoted line: “We have elected to put our money and faith in a mathematical framework that is free of politics and human error 17.” Another motto used by bitcoiners is Don’t Trust, Verify. This phrase has been around since the 1990s 18 and may have started as a twist on Ronald Reagan’s “trust, but verify 19.” It encourages users to independently verify the integrity of new open source software, and in the case of bitcoin, to verify the validity of transactions on the blockchain. A forum post from 2013 originated the word HODL, which now refers to the commitment to the self-sovereign act of holding on to one’s “stash” of bitcoin, no matter the volatility 20. Finally there’s the mantra Not Your Keys, Not Your Bitcoin, which refers to the lack of trust in third party custodians 21.

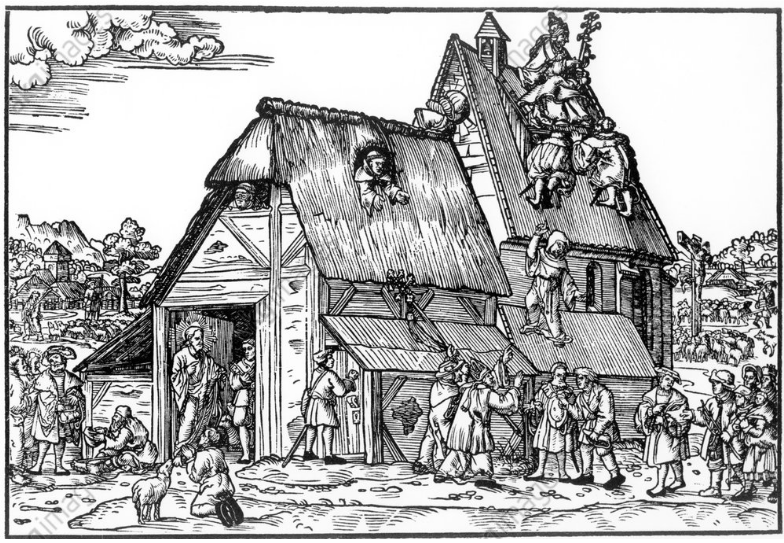

“Christ and the Sheep Shed”, 1524, Nurenberg. This popular woodcut propagandizes how believers by faith alone will be welcomed by christ, while the Catholic church is shown as pillaging the shed and cashing in on indulgences.

“The whole idea of having an independent currency, rather than just more private or censorship resistant payments for existing currencies, didn’t exist among either cypherpunks or academic cryptographers until libertarian futurists introduced it.”

— Nick Szabo, 2019

Financial Economy During A Reformation #

In the Reformation we saw the emergence of a new cultural and economic class trying to defend itself in a dynamic, volatile and hostile environment. It was a network of idiosyncratic economic actors, highly invested in their cause, cut off from traditional ways of doing business, with highly potent defenses at their disposal. Driven by a ferocious demand for increased financial security, this resulted in a number of innovations and secular trends. Below, we discuss several characteristics of the 16th century Dutch financial economy, and extrapolate from them some likely parallel trends that could sustainably emerge in the bitcoin space.

Marinus van Reymerswale, “The Tax Collector,” 1542

Deposit Banking: Full Reserve, Strict Protocols #

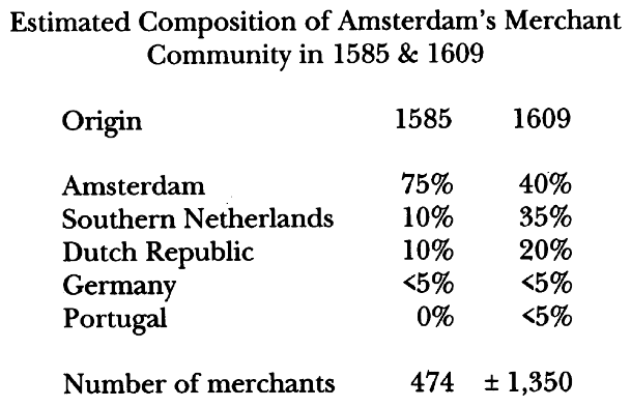

In 1609 in the Netherlands, merchants and city officials collaborated to found the Amsterdam Wisselbank (AWB). It served two main purposes. First, to guard the gold and silver wealth carried by the many hundreds of merchant refugees from the Southern Netherlands and other territories. Second, it would issue internationally trusted, florin-denominated bank money and bills of exchange.

“It is no wonder that these Dutchmen should thrive before us. Their statesmen are all merchants. They have travelled in foreign countries, they understand the course of trade, and they do everything to further its interests.”

— 17th century petition presented to Oliver Cromwell

The level of security of the AWB at the time was unparalleled in the world. It was located in Amsterdam, a city protected by the Dutch Waterline, which formed a moat over 50 miles long. The bank’s vault and operations were located at the town’s most central and visible location: city hall. And the bank’s organizational structure reflected a strong desire to be uncompromising in its fiduciary duties. The AWB counted four commissioners, and it was prohibited for the physical office to ever be staffed alone. The commissioners supervised four bookkeepers, four counter-bookkeepers, three receivers and a precious metal assayer. To prevent fraud, each of the bookkeepers was only responsible for a designated task 22. The VOC trading company, arguably the most powerful economic entity of its day, was an AWB account holder and it only made payments through the Wisselbank 23.

Despite a somewhat blemished track record as a full reserve bank, the reputation of the AWB was unparallelled in the 17th century, and its stability and reliability played a key role in the prosperity of the Dutch Republic. As late as 1820, Adam Smith in The Wealth of Nations praised the money of the Wisselbank for “its intrinsic superiority to currency.” The AWB was not cheap: it charged a 1% annual storage fee for gold coin, as well as opening fees, transaction fees, and a 1.5% withdrawal fee. Overall, the advantages of the AWB’s bank money were such that its banknotes carried an agio — they traded at a premium versus the actual gold and physical coins they were backed by.

Cart used to transport gold coins at the Amsterdam Wisselbank

In the bitcoin community, in response to a cultural aversion of trusted third parties, high risk of theft and loss, and long-term regulatory uncertainty, we expect increased adoption of highly secure, trust-minimized bitcoin deposit banking solutions.

The most trust-minimized solutions are those whereby theft or fraud is, by design, rendered extremely difficult. With the use of delay mechanisms and programmable nesting of signing authority, we’re seeing the beginning of a compelling and robust custody suite for bitcoin, which can generate a hitherto unparallelled level of security. We believe there is a lot of promise in the smart contract solutions recently explored by people such as Bob McElrath 24, Bryan Bishop 25, and Pieter Wuille 26. In that sense, the growing adoption of multi-sig addresses for bitcoin storage is likely a promising start of a much bigger trend. As of October 2019, 32% of all bitcoins in circulation are stored in the more privacy-friendly P2SH address format, and 12% are visibly stored in multi-sig addresses (up from 0% in 2014) 27.

“[…] a transaction setup scheme that binds both the user and the attacker to always using a public observation and delay period before a weakly-secured hot key is allowed to arbitrarily spend coins. During the delay period, there is an opportunity to initiate recovery/ clawback which can either trigger deeper cold storage parameters or […] reset the delay period.”

— Bryan Bishop describing multi-sig, pre-signed vault proposal, 2019

Enterprise Insurance: Cautious Web Of Trust #

With the 16th century seeing an explosion in maritime trade, it also meant that financial technology was needed to deal with the accompanying risk. The earliest forms of maritime insurance were in the form of “sea loans,” which commanded a high interest rate as they were only repaid upon a boat’s safe arrival at destination. This type of contract was especially useful if the investor did not have access to full information about the profitability of the sailor’s venture. An alternative was the “comenda” contract, which gave the investor the right to share in the profits of a voyage in the case of a successful completion. Both were imperfect substitutes of maritime insurance 28. Early insurance contracts have been found in Italy, where merchants themselves acted as underwriters — which later gave rise to the mutual form of insurance. By the sixteenth century, insurance had spread to Britain, France, Holland, and Spain. One recurring challenge for the merchants was with claim collection; some financial centers proved less reliable than others and a merchant went with the wrong underwriter he might never see his money. Given how hard essential information was to come by in the immature shipping market, the agency risk for underwriters was substantial. Sometimes merchants would deliberately over-insure and sink their ship, or they would buy insurance on a ship they knew was already lost. Because of the high risks involved, merchants paid a premium for quality underwriters, and underwriters would often confine themselves to working with mer- chants they could trust. Other factors that determined insurance rates were the financial stability of the underwriters and the city’s rule-of-law culture. Insurance broker licensing and guilding was repeatedly tried by authorities in Amsterdam and Venice, but remained largely unpopular.

Depiction of a Dutch merchant ship by Willem van de Velde (detail), 1650

Dutch VOC merchant and his wife, by Aelbert Cuyp, 1640-1660

Insurance in the bitcoin industry is still in a very early stage. Since the advent of the bitcoin mining industry in 2013 we have seen many examples of proto insurance contracts: investors will pre-order mining rigs from mining startups, who use the proceeds to produce the chips and manufacture the machines, and, similar to 16th century maritime trade, upon successful completion of the mission, are then able to share in the venture’s profits. Also several bitcoin custodians have some form of insurance, but the fine print often shows that it’s only the hot wallets that are insured—which usually represents less than 10% of the bitcoin under management. Similar to 16th century commerce, there are a plethora of unknowns when it comes to underwriting risk in the space: price volatility risk, regulatory risk, infosec risk, service provider risk, and so on. Given how globally saleable bitcoin is, even nation state level attacks cannot be ruled out. Insurance providers that are successful in this space will have to be extremely knowledgeable about both operations and technology, and will need to work within a framework that guarantees accountability and long-term relationships. It is no coincidence that self-insurance in the form of a reserve fund has become a staple of the bitcoin custody industry.

“While there is in excess of $500M of ‘traditional’ crime and $2B in specie capacity in the market, there is only around $150M of crime and $500M of specie cover available for crypto risks. ”

— AON director Jeff Hanson, July 2019

Liquid Collateral As Basis For Lending & Derivatives #

In 1602 merchants from the Netherlands merged together six small companies and pooled 64 tonnes of gold to form the Dutch East India Company (VOC). The VOC’s mission was to own and operate a fleet of merchant ships to trade with Asia, for which it received monopoly privileges by the Dutch government 29. The monopoly allowed the fleet to play a military and economic role in the ongoing war with Spain. In 1604 the company did a public offering — the first modern IPO — allowing any buyer to own its shares. It was a success: in Amsterdam, over 2% of the population subscribed 30. The deliberate absence of bearer shares and the clear ownership and transfer rules fulfilled key requirements for a transparent market 31. In 1610 the first dividends were paid to investors.

“The drop in interest rates demonstrates the success of Amsterdam’s secondary market, funneling a tidal wave of capital into productive purposes, notably short-term loans, by virtue of a vigorous securities trade with allied credit techniques.”

— Gelderblom & Jonker

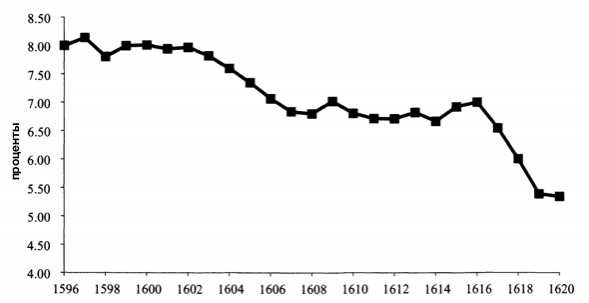

The VOC shares proved highly liquid and desirable as collateral: within months after the company’s foundation, shares valued at 27,600 guilders were used as surety in a prisoner exchange deal. And in 1607 a nobleman borrowed 2,000 guilders at 8% against 3,000 guilders worth of VOC shares as collateral (LTV ratio of 66%). The collateral market for VOC shares was very active, but because it was a private market not many records survived. By 1623 the government specifically regulated the procedure for VOC share liquidations in the case of loan defaults by their owner, and by the 1640s the Amsterdam stock exchange had a regular repo trade operation for VOC shares. Interest rates on the Amsterdam market for (secured) loans dropped from 8% in 1596 to under 6% in 1620. The deep liquidity of the VOC market also made them the perfect underlying asset for a flourishing derivatives market in 17th century Amsterdam, with forwards (including shorting), options, and repo contracts. In his VOC focused dissertation, historian L.O. Petram concludes that “after the period 1630-50, investors were primarily interested in the financial services the secondary market provided, rather than in the East India trade itself 32.”

Investments & returns of the pre-VOC trading companies. Gelderblom & Jonker, 2004

The new supply of loans collateralized by VOC shares caused Amsterdam interest rates to drop sharply. Gelderblom & Jonker, 2004

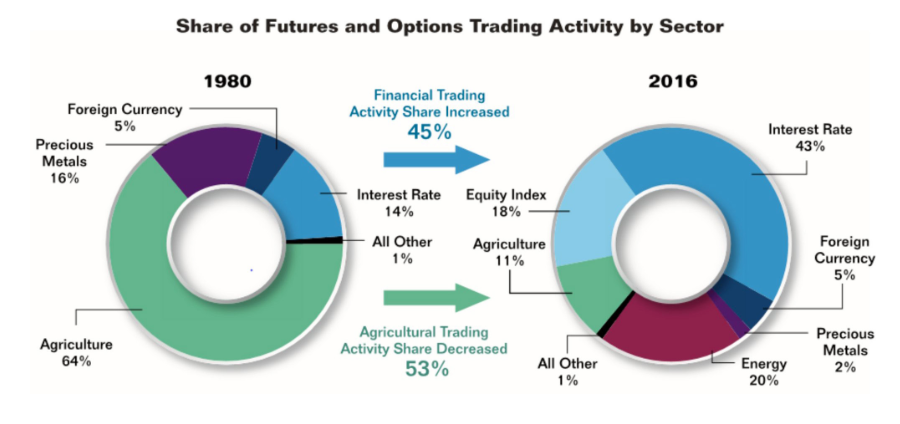

Shifting over to today, we see similarities between bitcoin savers and the historical VOC shareholders: they are often long-term committed, they have a relatively high concentration of their wealth tied up in the asset, they don’t like to sell it as that triggers capital gains taxes, and as millennials they have ambitions to make further investments. Going forward, we expect the use of bitcoin as collateral for borrowing to become increasingly widespread 33. We are also bullish on bitcoin derivatives markets, as it allows businesses to precisely tailor their risk management strategy as they pursue sustainable growth in the bitcoin industry. Our hypothesis is that the sectors in which price volatility impacts an economy the most will grow the largest derivatives markets: VOC shares in 16th century Amsterdam, agriculture and precious metals in 1980, interest rates today, and tomorrow perhaps bitcoin.

It is our hypothesis that derivatives markets grow around those sectors that are the greatest contributors to pricing risk in the economy (i.e. those economic goods that companies need to hedge against). Src: CFTC, “Commission in brief”, 2016.

Access To Capital In A Deflationary World #

Life annuities are contracts that are sold for a fixed price, giving the issuer the right to receiving regular payments for as long as he lives. They were frequently used from the 14th century onwards as loan substitutes, because they didn’t violate the Catholic Church’s ban on usury 34. (From the 16th century, the law usually guaranteed that perpetual annuities could be cancelled by paying back the capital sum.) Life annuity contracts were often used to fund capital-intensive enterprises that had a relatively low risk profile: businesses, farms, and local governments. In the 14th century Lowlands, two economic profiles emerged. In the coastal area, with sandy soils and regularly pestered by floods, many landowners borrowed themselves into eventual expropriation. In the more stable interior of Flanders, annuity-based credit was used for accelerating business development (most often to unlock a real estate investment), while older inhabitants would buy the contracts as a form of retirement income. Annuities could be transferred to third parties and thus became a popular financial instrument among the urban population. As the Dutch Revolt came into swing, and as income from maritime trade increased, the protection of cities and their citizens became more important, and cities would raise capital by means of issuing annuities.

“By the 1580s annuities were sufficiently well established to serve as trusted instruments for a diverse public, including merchants, widows, orphans, and charity institutions.”

— Gelderblom & Jonker, 2004

An important reason why annuities were popular so much earlier than mutual life insurance (which only emerged in 18th century England), was that it requires a lot more trust in the entity providing the policy — the insured needs to literally trust them from beyond the grave, and there is no collateral that can be clawed back. There was potentially a cultural component as well, where customers felt more comfortable betting on a long life (annuity) than betting on a shorter one (life insurance).

“Annuities could be used for a variety of purposes, in particular as a means to settle balances among heirs […] In the surroundings of Antwerp, the exceptional growth of the city had a strong impact on the local market for land and credit via the massive participation of townsmen.”

— Limberger & De Vijlder, 2018

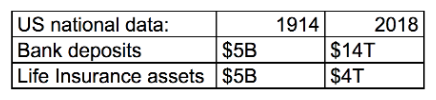

Having only recently passed its 10th anniversary, bitcoin denominated lending is alive and well. Genesis Capital reportedly generated over $2 billion worth of bitcoin-denominated loans and borrows since launching in March 2018 35. We’re seeing demand coming from hedge funds, businesses with bitcoin inventory, and individual traders. We see a parallel between historical annuities issued by Dutch cities and today’s IEO tokens, which stands for “Intial Exchange Offering 36.” For example Bitfinex created an IEO token (called LEO) in order to tap the market for liquidity during a legally challenging time, as well as to de-risk its Tether related liquidity problem 37. By making an open-ended offer to repurchase LEO tokens at market value, this token has annuity-like characteristics. Other offshore exchanges have done the same: Binance created an offering with Binance Coin, Huobi launched Huobi Token, and FTX has FTX Token 38. Bitcoin exchanges often have loyal customer bases which depend on their services to some extent, and these tokens allow them to tap into that trust by in effect borrowing from the public. In analogy with the embattled Dutch towns and the income hungry merchants, we expect a continued popularity of these annuity-like offerings among offshore bitcoin exchanges and crypto trading millennials. In fact, they are the first examples of proto life insurance products in the bitcoin marketplace. Over time we expect the emergence of life insurance mutual companies, which might very well breathe new life into the severely weakened traditional life insurance industry. Studies have repeatedly shown that inflation dampens demand for life insurance over time, and so conversely if bitcoin-as-hard-money sees widespread adoption, it is logical for life insurance products to become highly popular once more.

“An IEO is like Goldman Sachs crashing into Nasdaq. It’s a new breed of fundraising that could potentially change what’s happening in finance […] but regulations have to be figured out.”

— Steven Nerayoff, CEO Alchemist, June 2019

Sources: Sixth Annual Meeting of the Association of Life Insurance Presidents, https://www.iii.org, ycharts.

“A 1 percentage point rise in inflation is expected to be accompanied by a 1.20 percent decline in net real life insurance in force per capita.”

— UC Berkeley prof. David Babbel, 1981

Conclusion #

Venture Capitalist Eric Weinstein recently opined that the adage “good ideas beat bad ideas” is false, and that the correct formulation is rather “fit ideas beat unfit ideas 39.” He’s making the Darwinian point that, similar to the survival chances of animal species, an idea will only flourish when the circumstances are exactly ripe for it.

And indeed, history shows the quality of an idea in itself is not enough for it to blossom socially. A working steam engine was described by Hero of Alexandria in the 1st century BC, and yet it was only commercialized 1,600 years later. The movable type printing press already existed before Gutenberg’s machine, in 14th century Korea - yet didn’t lead to a revolution there. And centuries before Columbus and Hudson, the vikings had already landed in America. In other words, often circumstances are such that a highly potent idea just doesn’t make into popular adoption.

But once in a while, the puzzle of circumstance fits together in a peculiar way, creating fertile ground for many ideas to be adopted at once, and allowing for a spectacle of chain reactions that profoundly reshapes society. The Protestant Reformation was such a time: ideas germinated, rebellion erupted, wounds healed, and a generation of radical entrepreneurs produced an unprecedented series of foundational economic and financial innovations. This happened 500 years ago, and it may be happening once more.

“If the potential of a startup is proportionate to the size times the incompetence of its competitors, the most promising startup of all would be one that competed with national governments. It’s not impossible; this is what cryptocurrencies do.”

— Paul Graham, founder YCombinator, Aug 2019

Today we see broad parts of society, millennials especially, acting increasingly critical of central bank interventionism. At the same time technologists, at an accellerating pace, are developing an array of tools that allow for disruption of the economic status quo. In a decade the millennial generation is projected to have the highest earning power of all generations, and this tech-savvy post 9/11 generation has encryption to its disposal as a defensive technology. Meanwhile the bitcoin ecosystem is maturing in all aspects of its economy, in particular in deposit banking, insurance, lending and derivatives, and early forms of life insurance. If this process persists, bitcoin’s layered protocol suite could become a global powerhouse and potential alternative to the IMFS.

Are you ready for the Bitcoin Reformation?

Appendix #

Brief chronology of the Protestant Reformation, with focus on the Low Countries.

1. Early Dissent #

In 1511, Erasmus of Rotterdam publishes the wildly popular “Praise of Folly,” a bold satire of the Catholic church 40. Six years later in 1517 Martin Luther goes public with his “Ninety-Five Theses,” a scathing criticism of the rent-seeking practices of the Catholic Church 41. Within months, thousands of copies circulate throughout Europe. In response to this perceived heresy against Catholicism, the first book burnings take place in 1521 42. In 1522, king Charles V institutes the Inquisition in the Low Countries for the suppression of heretics 43. In 1523 we see the first heretic executions by fire 44. In 1535 Charles V condemns all heretics to death, and in 1539 he cracks down on the tax revolt against him in Ghent.

During this time, no social stratum is free from the politics of suppression; even devout Flemish Catholic Gerardus Mercator (the cartographer famous for his 1569 world map) is prosecuted by the inquisition in 1543 and spends seven months in prison until he is released based on lack of proof. In that same year, Copernicus publishes his book on heliocentric theory, and Flemish anatomist Vesalius fundamentally challenges Galen’s anatomical model for the first time in fifteen hundred years.

In his painting “Ship of Fools” (1500), Hieronymus Bosch places members of the clergy in the spotlight. The foreword to the satirical poem it was likely inspired by, Stultifera Navis from 1497, says: “Who takes his place on the ship of fools, sails laughing and singing to hell 45.”

In 1548 humanist Christoffel Plantijn moves to Antwerp—his book publishing house will quickly become the most prestigious in Western Europe 46. In 1555 we see the founding of the first underground protestant municipality in Antwerp.

2. Open Rebellion #

In 1559 the Hapsburg king departs Brussels and leaves for Spain, after which his half sister Margareta becomes governor of the Netherlands. 1566 becomes known as the “miracle year.” It begins with Flemish nobility sharing a no-prosecution petition with the governor of the Netherlands, which yields a mild reaction. Emboldened, protestant factions start preaching inside catholic churches, with accompanying vandalism later known as the iconoclasm. A local truce is reached without the governor’s consent and protestants are allowed to preach in six churches within Antwerp’s city walls 47. Later that year, the defeat of an army of protestants (geuzen) starts tilting the power back in favor of the royalists.

“The audacity of the Calvinist preachers in this area [of Flanders] has grown so great that in their sermons they admonish the people that it is not enough to remove all idolatry from their hearts; they must also remove it from their sight. Little by little, it seems, they are trying to impress upon their hearers the need to pillage the churches and abolish all images.”

— Spanish government official, 1566 48

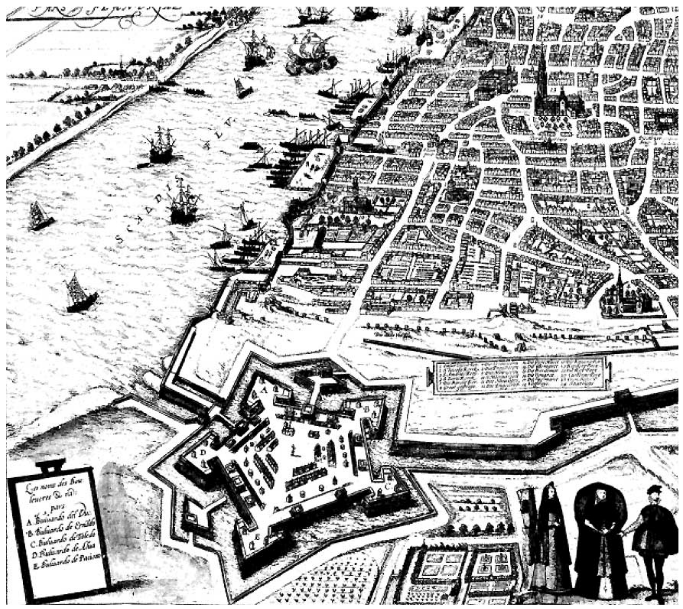

3. Crackdown #

In 1567, the Spanish Duke of Alba arrives in the Netherlands with an army of ten thousand Spanish veterans 49. He institutes a “Court of Blood,” and in his six year reign as Governor of the Netherlands is considered by some to be responsible for the death of over eighteen thousand people 50. Upon arrival in the Netherlands, Alba raises taxes and begins with the construction of a huge fortress on the edge of the city, which is completed in 1572. This pentagonal citadel becomes “one of the most studied urban installations of the 16th century 51.” Three years later, the Spanish crown is in financial trouble and stops paying its mercenaries in the Lowlands, who at the command of Antwerp Citadel’s commander Sancho D’Avila pillage the city of Antwerp in 1576 52. This “Spanish Fury” becomes one of the centuries’ worst atrocities, wherein 7-10% of the population is murdered in three days and a thousand houses are destroyed.

Allegory of the Dutch nation attacked by the Spaniards. Joannes Gijsius, 1616

Birds-eye view of Antwerp in 1572, featuring Alva’s citadel. Src: Civitates Orbis Terrarum I

This etch from 1580 shows how threatened the Dutch felt by the Spanish invaders, here depicted as a pig infestation. The lion was a symbol associated with the Netherlands 53.

Despite fierce resistance in the following years, including a partial destruction of the Spanish Citadel, in 1585 the City of Antwerp surrenders to Spain and all resident Protestants are given four years to settle their affairs and leave the city. The same happens in Ghent and Brussels. In the twenty years following the Sack of Antwerp, the city loses nearly 50% of its inhabitants to emigration 54. Europe’s strongest economy has just suffered a heart attack: for the next century, Antwerp wages remain 35% lower than for example Leiden, a city merely 85 miles away yet in Protestant-friendly Northern Netherlands 55.

4. Netherlands, New Amsterdam, New York #

The fall of Antwerp and the rest of the Southern Netherlands helps kickstart the Dutch Republic’s golden age, by virtue of the influx of some 50-100,000 Flemings 56. Simultaneously, England, a relative religious safe haven, sees its human capital boosted by waves of inbound migration 57. After decades of war and conquest, the Spanish empire has weakened internally (in part due to the health consequences of inbreeding 58) and its strong hierarchy-based rule proves no match for the nimble, dynamic, and commercially oriented organization of Dutch and British economies. The combination of religious and commercial tolerance on the one hand, and a defensible territory surrounded by water on the other, proved to be a recipe for success, and for the next 200 years, the Netherlands and England are at the forefront of economic innovation and growth.

“Half of the merchants with property worth ƒ100,000 or more in 1631 originated from the Southern Netherlands 59.”

“The course of events in Holland after 1600 runs counter to common opinion about the importance of a publicly traded government debt as the origin of secondary markets. The VOC shares provided the crucial breakthrough, not government bonds.”

— Gelderblom & Jonker, 2004

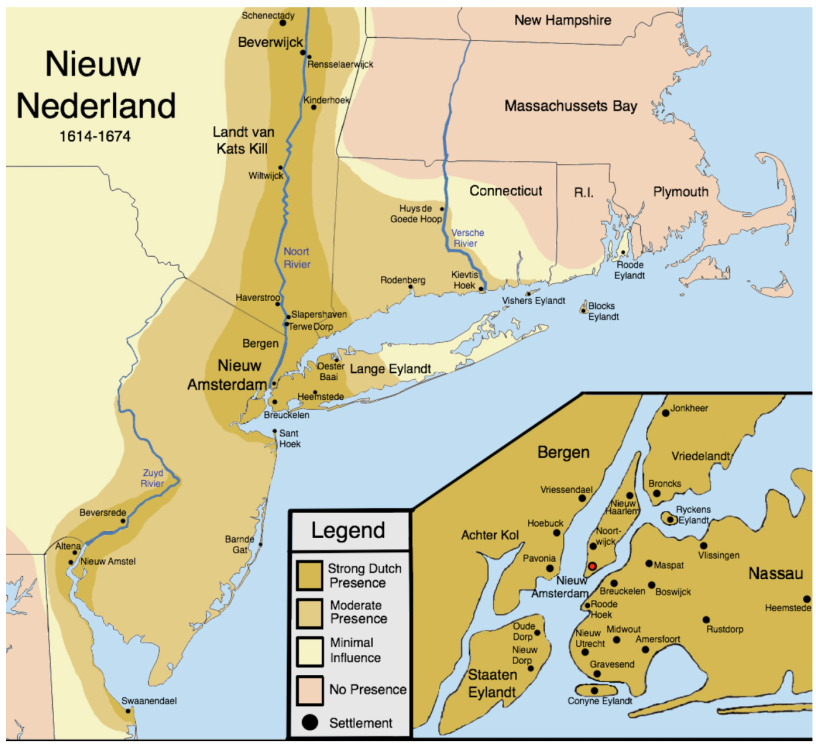

In 1579 the Northern Dutch provinces gather to sign the Union of Utrecht, in which they assert their independence from Spain. The document declares complete religious freedom in the Dutch territories, a freedom which will also come to be respected in New Amsterdam. In 1588, after the destruction of its mighty Armada in the British Channel, Spain gives up on its quest to conquer England. In 1602, the Dutch East India Company is founded, among others by Dirck van Os, an Antwerp immigrant. Van Os also helps fund Henry Hudson’s 1607 expedition to North America, signs his name on one of the world’s oldest stock certificates, and co-founds the Amsterdam Exchange Bank (1609). In that same year 1609, a peace treaty is signed between Spain and the Dutch Republic. In 1620 the Pilgrim Fathers, who would later sail on the Mayflower and found the Plymouth Colony, settle in the Dutch City of Leiden where they find refuge from religious intolerance in their native England. In 1621 Flemish-Dutch merchant Willem Usselincx obtains permission from the Staten Generaal to found the Dutch West India Company (WIC), with a monopoly on the exploration of North America. In 1624 the first Dutch settlers arrive on Governor’s Island, outside of Manhattan. In 1626 Walloon Peter Minuit purchases Manhattan Island from the Lenape Native Americans, and chooses it as the capital of New Netherland - which at that time still was a purely commercial enterprise. In 1638, after the manuscript is smuggled out of Italy, Galileo Galilei’s heliocentric “Two New Sciences” is published in Holland. In 1643 Isaac Jogues estimates Manhattan’s population at five hundred and the number of languages spoken there at eighteen 60. In 1644 English poet John Milton publishes Areopagitica, a philosophical defence of freedom of speech and expression. In 1654 a small group of Portugese Jews arrives in Manhattan, and after the Jewish community petitions the WIC back in Europe, the New Amsterdam governor Peter Stuyvesant eventually agrees to let them stay, setting a welcoming precedent for future non-Dutch settlers 61. In 1664, New Amsterdam is conquered by the British army and is renamed as New York—the population is nine thousand at the time 62. In 1665, Spinoza’s teacher and Flemish refugee Franciscus Van Den Enden publishes “Free Political Theses,” in which he defends freedom of speech, freedom of religion, egalitarianism, abolitionism, and direct democracy. In 1683 British earl Thomas Dongan is appointed as governor of New York and tasked to promote the Anglican Church there — he never succeeds 63. In 1689 John Locke publishes “A Letter Concerning Toleration,” in which the philosopher makes a highly influential case for religious tolerance. In 1777, New York adopts the first State Constitution without any religious establishment and becomes the only revolutionary state that does not have a religious test for office holding 64.

Map of New Netherlands - the Dutch presence was the greatest in the area currently known as New York City.

“Give me the liberty to know, to utter, and to argue freely according to conscience, above all liberties.”

— John Milton, 1644

“This convention doth further […] ordain, determine, and declare, that the free exercise and enjoyment of religious profession and worship, without discrimination or preference, shall forever hereafter be allowed, within this State, to all mankind.”

— New York State Constitution, 1777

At the heart of Bruegel’s “The Battle between Carnival and Lent” a married couple is shown. The man carries a sack, symbolizing egotism and imperfection, and the woman an unlit lantern, signifying absence of wisdom. Accompanied by a fool and kindly supporting each other, they wander off. Interpreting his pictography, we see a supportive message about the future of the Reformation: While the common man and woman aren’t as enlightened as the intellectual classes want them to be, they generally do not participate in tribalist warfare. And this disengagement isn’t informed by general apathy, but rather by a pragmatic interest in peaceful family life and individual economic progress.

With Bruegel, we are compassionately optimistic about long term improvement of the human condition, even in the case of a Reformation 2.0. Sure, society teems with prejudice and poor judgement on both sides of any argument—but given a long enough time horizon, burdens of bigotry and fanaticism can be offloaded, and lanterns of reason can be lit.

The journey of history meanders, ever allowing for forks with better world potential.

An Economic Analysis of the Protestant Reformation, Authors: Robert B. Ekelund, Jr., Robert F. Hébert, and Robert D. Tollison. Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 110, No. 3 (June 2002), pp. 646-671 ↩︎

The term “International Monetary and Financial System” is often used by the Bank for International Settlement, but dates back at least to 1984, where it shows up in a report issued by the Group of Twenty-Four, “A Revised Program of Action Towards Reform of the International Monetary and Financial System. ↩︎

See Dittmar & Seabold, “Gutenberg’s moving type propelled Europe towards the scientific revolution” in LSE Business Review, 2019. ↩︎

See for example “Notes on the Origin of Double-Entry Bookkeeping” by Basil S. Yamey, 1947. ↩︎

See “An Analysis of Navigational Instruments in the Age of Exploration,” Lois Ann Swanick, 2005. ↩︎

See Dittmar & Seabold, ibid. ↩︎

Src: Business Communications Review, 2002 ↩︎

“The sixteenth century was marked by a strong expansion of intra-European trade and as well as the income elasticity, the price elasticity of export demand had risen noticeably. Hence, progressive areas which could offer better-quality products for relatively low prices naturally diverted the demand for specialized goods from more primitive areas.” Wee, H. V. D. (1975). Structural Changes and Specialization in the Industry of the Southern Netherlands, 1100-1600, p. 216. ↩︎

See “Millennials + money: The unfiltered journey,” Facebook, 2016. ↩︎

Src: “18th Annual Transamerica Retirement Survey,” 2018. ↩︎

Src: “Bitcoin is a Demographic Mega-Trend: Data Analysis,” Spencer Bogard, 2019. ↩︎

Src: “Coming of age: how millennials are becoming a growing economic force,” Snapchat, June 18 2018. ↩︎

Already in the early nineties the link between the privacy provided by encryption and human rights was clearly recognized by the cypherpunk community. Phil Zimmerman in 1991: “When use of strong cryptography becomes popular, it’s harder for the government to criminalize it. Therefore, using PGP is good for preserving democracy.” Also see Eric Hughes in 1993: “We must defend our own privacy if we expect to have any. […] Cypherpunks write code. We know that someone has to write software to defend privacy, and […] we’re going to write it.” ↩︎

Src: Swire, Hemmings, Kirkland: “Online Privacy and ISPs,” 2016, and letsencrypt.org, 12/31/2019. ↩︎

Zhang, L., Zhao, L., Wang, Z., & Liu, J. (2017). “WiFi Networks in Metropolises: From Access Point and User Perspectives.” From the paper: “measurement shows that today’s metropolises already have dense deployments of wireless Access Points, which can collectively provide near-ubiquitous Internet access. […] we can foresee that in the near future wireless mesh networks may be constructed and maintained at the metropolis level with the help of mobile wireless APs that can be carried by vehicles or whose role can be fulfilled by increasingly capable personal mobile devices.” ↩︎

Origin is the Bitcointalk forum, May 2011. Later popularized by the Casascius physical bitcoins. ↩︎

New York Times, 2013/04/11, interview by Nathaniel Popper. ↩︎

E.g. see Shiu-Kai Chin, “High-Confidence Design for Security: Don’t Trust - Verify,” 1999. ↩︎

“I AM HODLING”, GameKyuubi, Dec 2013, Bitcointalk.org. ↩︎

Possible origin is a 2014 discussion on reddit.com, entitled “PSA: if you don’t own your private keys, you don’t own your bitcoin.” It has also been attributed to Andreas Antonopoulos. ↩︎

Over time, in violation of its original charter, the AWB secretly wrote out unsecured loans to the Amsterdam City Counsel, the Dutch Government, and to the VOC. By the year 1669 it only had a reserve ratio of 57%. These risky practices would in the long run lead to its demise. Src: “How Amsterdam got Fiat Money,” Quinn & Roberds, 2010. ↩︎

Source: https://www.beursgeschiedenis.nl/en/moment/the-bank-of-amsterdam/. ↩︎

Bob McElrath, “On-Chain Defense in Depthm” talk given for Bitcoin Switzerland on 01/25/2019. ↩︎

Bryan Bishop, “Bitcoin Vaults with anti-theft recovery/clawback mechanisms,” email on bitcoin-dev list on 08/07/2019. ↩︎

Pieter Wuille, “Miniscript,” email on bitcoin-dev list on 08/19/2019. ↩︎

Src: https://p2sh.info. ↩︎

Src: Kingston, “Governance and institutional change in marine insurance, 1350-1850,” 2014. ↩︎

It became a monumental success: by 1669, the VOC had 150 merchant ships, 40 warships (for protection), and employed 20,000 people. Src: “Introduction to Financial Technology,” Roy S. Freeman, 2006. ↩︎

Src: “Completing a Financial Revolution: The Finance of the Dutch East India Trade and the Rise of the Amsterdam Capital Market, 1595-1612,” Gelderblom & Jonker, 2004. ↩︎

Over time, the Amsterdam Stock Exchange developed a “handshake protocol” to securely execute trades. It was described in a 1688 essay by trader Joseph de la Vega: “A member of the Exchange opens his hand and another takes it, and thus sells a number of shares at a fixed price, which is confirmed by a second handshake. With a new handshake a further item is offered, and then there follows a bid. The hands redden from the Blows.” Quoted in Freedman’s “Introduction to Financial Technology,” p. 4. ↩︎

Src: “The world’s first stock exchange: how the Amsterdam market for Dutch East India Company shares became a modern securities market, 1602-1700,” L.O. Petram, 2011. ↩︎

It is perhaps notable how in the aforementioned example of the 1607 loan with VOC shares, the loan-to-value ratio of 66% is similar to what for example Unchained Capital uses as minimum bitcoin collateral. See https://www.unchained-capital.com/loans/. ↩︎

See “The Use of Perpetual Annuities in Rural Brabant in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries,” Limberger & De Vijlder, 2018. From the 16th century, the law usually guaranteed that perpetual annuities could be cancelled by paying back the capital sum—this made them even more similar to loans. ↩︎

See genesiscap.co, “Digital Asset Lending Snapshot” 2019 Q3 Insights. ↩︎

Fore an explainer, see Gertrude Chavez-Dreyfuss, “Initial Exchange Offerings Flourish in Crypto Market,” June 20 2019. ↩︎

See https://www.bitfinex.com/wp-2019-05.pdf and https://leo.bitfinex.com/. ↩︎

See https://www.binance.com/resources/ico/Binance_WhitePaper_en.pdf. ↩︎

See https://twitter.com/EricRWeinstein, tweet of Aug 24, 2019. ↩︎

“Praise of Folly had appeared in 36 Latin editions by 1536,” Egbertus Van Gulik, “Erasmus and His Books,” 2018, p.118. ↩︎

“Vatican archives reveal that around 1512, wealthy banking families, such as the German Fuggers, became papal agents for the collection of indulgence receipts and other forms of taxes. The kind and severity of taxes multiplied as the Middle Ages wore on. Temporary levies became permanent, and many new taxes were imposed on the wealthiest church members. […] In addition to the market for indulgences, evidence also abounds of rent seeking in the marriage market. Endogamy and marriage regulations were manipulated in order to produce as high a rent as possible by attaching “redemptive promises” to the marriage contract.” From “An Economic Analysis of the Protestant Reformation,” Journal of Political Economy, 2002, p. 656. ↩︎

Src: Inge De Moor, “De kracht van het protestantse woord: Het succes van de hagenpreken in Antwerpen en Gent,” 2010. ↩︎

Src: Amy Eberlin, “Flemish Relgious Emigration in the 16th/17th Centuries.” ↩︎

“The Netherlands had by far the most repressive anti-heresy legislation in Europe — between 1523 and 1566 at least 1,300 people had been executed, and thousands more had been indicted, fined or banished.”, from Judith Pollmann, “Countering the Reformation in France and the Netherlands,” 2006. ↩︎

Src: “Hieronymus Bosch: Visions of Genius,” Ilsink & Koldeweij ↩︎

Plantijn’s motivation for moving to Antwerp: “No other town in the world could offer me more facilities for carrying on the trade I intended to begin. Antwerp can be easily reached; various nations meet in this marketplace; there too can be found the raw materials indispensable for the practice of one’s trade; craftsmen for all trades can be easily found and instructed in a short time.” Source: “From Antwerp and Amsterdam to London: The Decline of Financial Centres in Europe,” Peter Spufford, De Economist 154, 2006, p.155. ↩︎

Geoffrey Parker, “The Dutch Revolt,” pp.74-76 ↩︎

This is considered to be the start the 80 Years’ War, or the Dutch War of Independence. Over the next 5 decades, Spain would send a total of 140,000 soldiers to the Netherlands. At its peak, in 1574, the so called Army of Flanders counted 86,235 soldiers. Source: Geoffrey Parker, “The Army of Flanders and the Spanish Road, 1567-1659,” 2004 ↩︎

See “The Spanish Road to the Netherlands,” Geoffrey Parker, 2012. ↩︎

Source “Cities at War in Early Modern Europe,” Martha Pollak, 2010, p.14. ↩︎

The rumor was that a treasure fleet carrying the Spanish soldier’s pay was intercepted by Dutch Sea Beggars, offering a justification for the Sack of Antwerp. See “From Criminal to Courtier: The Soldier in Netherlandish Art 1550-1672,” David Kunzle, p. 145. ↩︎

Source: “The Duke of Alba: The Ideal Enemy,” Daniel R. Horst, 2014. The Dutch verse under the image translates in part: “Stop rooting in my garden Spanish boars - Turn your pig’s back around and leave - Or my beggar’s bludgeon will teach you a lesson - It will break your head or stretch your neck […] Run rogues run, or the beggars will force you.” ↩︎

Source: “Antwerpen in de tijd van de Reformatie,” Guido Marnef, 1996, p.25: https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/marn002antw01_01/. ↩︎

See “Prices and wages as development variables: A comparison between England and the Southern Netherlands, 1400–1700,” 1978, p. 93. In part because of the import tolls levied by the Dutch Republic (1587-1863) on any mercantile merchandise destined for Antwerp, the population fully didn’t recover from its 16th century peak until the 1850s. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Antwerp#Historical_population ↩︎

Some examples are Justus Lipsius (first dean of Leiden University), Dirck van Os, Franciscus van den Enden (teacher of Baruch Spinoza), and Judocus Hondius (cartographer of the New World). See also data from St. Andrews Institute, and the article “Innovation through Migration: The Settlements of Calvinistic Netherlanders in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century Central and Western Europe” by Heinz Schilling, 1983 ↩︎

See “Complexity and diversity: domestic material culture and French immigrant identity in early modern London,” Greig Parker, 2013. ↩︎

See “The Role of Inbreeding in the Extinction of a European Royal Dynasty,” 2009. ↩︎

Source: OC Gelderblom, “The Contribution of Merchants from the Southern Netherlands to the Commercial Expansion of Amsterdam,” 2003. ↩︎

Src: Collin Woodard, “American Nations,” 2011. ↩︎

See Paul Finkelman, “The Roots of Religious Freedom in Early America: Religious Toleration and Religious Diversity in New Netherland and Colonial New York,” 2012 ↩︎

“The Duke’s colony was probably the most polyglot in the New World. In addition to the Dutch Reformed majority, a religious census at the time would have found Lutherans from Holland and Sweden; French Calvinists, Presbyterians, Puritans, Separatists, Baptists, Ababaptists, Quakers, and a variety of other Protestant sects from the British Isles and elsewhere; and small numbers of Jews and Catholics.” […] “Toleration in New Netherland had almost no theory or philosophy behind it. It evolved out of the need to populate a frontier and encourage trade and commerce. Put simply, the Dutch West India Company valued worldly success above theology.” - Finkelman, 2012 ↩︎

See Finkelman, 2012. ↩︎

See Finkelman, 2012. ↩︎